BACK TO ESSAYS

Frugal and Fashionable: Quiltmaking During the Great Depression

All quilt collectors are familiar with what are often called Depression Quilts. The quilts are recognizable because of their color scheme, a scrappy collage of pastel prints and plains, pulled together with plain white cotton as the neutral shade. A collection of stereotypes clings to Depression Quilts and their makers. As the name implies, the quilts are believed to be a product of the Great Depression that lasted from 1930 to 1940. Quilts were popular during hard times because quiltmaking was a cheap hobby that made use of small scraps left over from other sewing. Makers often incorporated feedsack fabrics, which appear today to be the ultimate in recycling and frugality. The quilts were made to keep families warm during times when blankets were a luxury.

Although there is some truth to each of these frugal stereotypes, the current research being conducted across America by quilt projects indicates that our view of Depression Quilts is far too narrow. Even the name is wrong, as there is much evidence that the fashion for making scrappy, pastel quilts dates to about the mid-1920s and the style persisted until about the 1950s.

The mid-1920s fashionableness of quilts grew from a fascination with “colonial” antiques, inspired by a nostalgia for an imagined American past coupled with a developing pride in American arts and crafts. The colonial revival dictated maple bedsteads, Windsor chairs, rag rugs, and patchwork quilts in bedrooms across the country. Magazines advised homemakers to dig antique family quilts out of trunks in the attic and encouraged those who hadn’t inherited any to make their own heirlooms. The trendsetters advocated a return to old-fashioned standards for needlework, emphasizing the appliqué work and fancy quilting that had fallen from fashion during the nineteenth century as the sewing machine moved into the American home. They gave instruction for updating old patters with new color schemes, a changed summarized in the Nancy Cabot quilting column in the Chicago Tribune of July 16, 1933. In the “early days…only strong colors were available…A 20th century quiltmaker would undoubtedly prefer dainty pastel shades.”

By the time the Depression had arrived, quiltmaking was well established as a hobby for rural and urban women of all classes. The scrap look to these quilts can be explained by a fashion for a variegated look that is also found in the dishware of the times. The fashionable tableware designed by Russell Wright in the 1920s included simple dishes in a variety of bright or pastel shades. Fiesta ware is probably the best known of this style of dishware, but several other china lines made a virtue of mismatched plates.

In quilts the scrappy look was as much a trend as frugality. In fact, a large number of small pieces is an indication of the quiltmaker’s access to abundant fabric. Tiny pieces waste fabric as so much is incorporated into the seam allowance. The small scraps used in quilts are rarely left over bits from sewing, but pieces that have been deliberately cut down.

One could purchase the scrap look. Many magazines advertised packets of small scraps and factory cut-aways. Sears, Roebuck and Company sold a box of cotton prints with patterns like the Double Wedding Ring and Grandmother’s Flower Garden that made the most of the small pieces. Many scrap-look designs like the Trip Around the World, the Butterfly and the Fan were sold as kits with ready-cut pieces. Most people see printed feedsack fabrics in the Depression era quilts as more evidence of poverty, but the recycled print feedsacks were more prevalent during the wartime fabric restrictions of the 1940s.

The scrappy, light, bright look of the Depression quilts remained quite important during World War II and into the prosperous 1950s. The fact that quiltmakers in 1927 and 1947 made similar quilts makes it difficult for us to get a view of quilts actually made during the Depression. Unless the piece has a date inscribed or a detailed oral history with it, we can only date the light, bright quilts to a vague twenty-five year period – 1925 – 1950. To get an accurate perspective of quiltmaking during the Depression we can wish that the quilt project phenomenon had begun much earlier. If quilt days had been held in the 1930s we would know far more about how economic hardships shaped the look of quilts.

Merikay Waldvogel and I realized we had a window into the Depression with our research into quilts entered in a national contest sponsored by Sears, Roebuck and Company in the spring of 1933. During the worst months of the Depression, quilters from all over the country entered a contest that promised $1200 and the chance that their work would be displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair. Nearly 25,000 women entered.

Merikay and I became fascinated with the contest because of its size and the quality of quilts entered. As we collected information we realized that Sears, in essence, had conducted a huge national quilt day on May 15, 1933, the day entries were due at local stores. Unfortunately, very few of the 25,000 quilts were recorded or photographed, but many if not all of them received green ribbons, some of which have been handed down with the quilts as evidence of their entry.

Our search for contest quilts has yielded about 150. Of those, we have chosen thirty to exhibit in a traveling show sponsored by the Knoxville Museum of Art. From the 150 we have drawn many conclusions about quiltmaking in the spring of 1933.

We found that women from all economic classes entered; we heard stories from farm families forced by low commodity prices to move in with their parents and of doctor’s wives who made silk quilts in their Florida vacation homes. We found little evidence of quilts entered by women of color or by women who were immigrants. We have not yet found one quilt entered by a man (although we have found several collaborative quilts entered in the wife’s name).

We found that several women entered the typical scrappy quilts made of dress prints, but we were surprised to find how many women entered original designs pieced and appliquéd of expensive cottons obviously bought specifically for the quilts. Some well-to-do women (and we must recall that there were well-to-do women during the Depression) made these luxurious show quilts. Yet, we found far more women from working class or suddenly unemployed families to have made the fancy quilts. Women like unemployed seamstresses Frances Klemenz bought expensive cotton weaves that cost about three times the price of the less expensive dress prints. She spent months designing and stitching a basket of bleeding hearts that won a cash prize.

School teacher Lois Hobgood Crowell decided to enter because making a quilt sounded like inexpensive entertainment, despite the cost of the cottons bought specifically for the quilt. Married couples Linda and Clarence Rebenstorff and Edith and Ralph Matthews designed show quilts to take a chance on that lavish first prize.

We have found no correlation between economic class and the luxuriousness of the quilts. We did find many “art quilts” (to use a term popular today), quilts that commemorated World’s Fair themes in original and pictorial designs. Because the judges preferred more traditional quilts, these creative entries received little attention. We have speculated that less conservative judges might have given American women a completely different set of goals in their quiltmaking. Had original designs won prizes, the “Depression look” in quilts might have been far more creative.

In looking at the quiltmakers, we found much information about quiltmaking as a profession. Several of the women involved in the contest made a living for their families by making quilts. The first prize winner was a group project, coordinated by Margaret Caden who paid professional seamstresses a small price to piece, stuff and quilt her entry. We found that poverty did not create utilitarian quilts; rather poor women made elaborate quilts for pay.

Our research into quilts entered in the Sears contest has reinforced our views that rather than being merely a frugal response to an economic disaster, quiltmaking in the 1930s was also fashionable, a product of social and cultural factors far more complex than the clichés. Studying contests as if they were quilt days will give us a more accurate picture of our quiltmaking past and present.

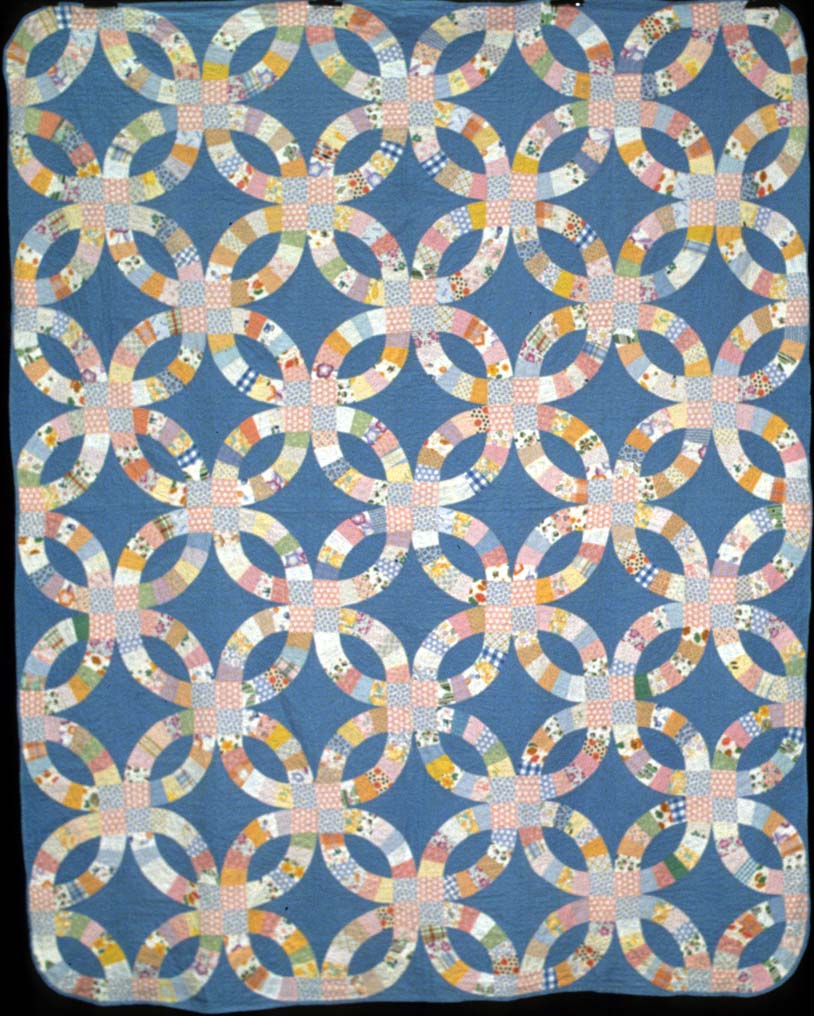

Double Wedding Ring

Rebecca M. Fraser Cooper

Seward County, Nebraska

Date

Collection of the National Quilt Museum acc.#

Family members recall that Rebecca Cooper made this quilt in 1931 and 1932 as a gift for her minister. She chose one of the most popular depression-era designs, but her choice of blue as background is unusual. Many scrappy quilts were pieced to white backgrounds.

Dogwood

Martha Louisa 'Lydia' Pogue Moffet Moffett

1932

Collection of the DAR Museum acc.#99.49

In the depths of the Great Depression in 1932, Lydia finished this fancy quilt made from a pattern sold by designer Marie Webster. Webster first designed the quilt for the Ladies Home Journal in 1912 and managed a cottage industry selling quilt patterns until 1942.

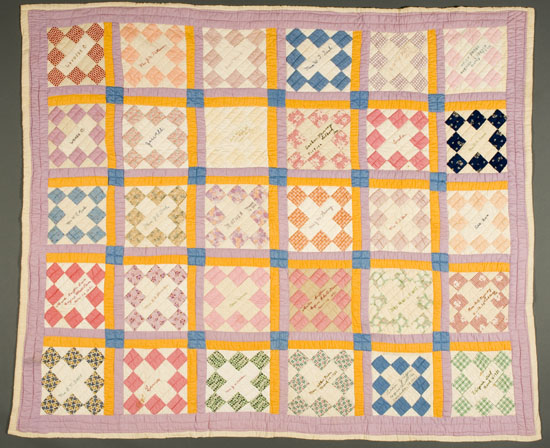

Pieced Friendship Album

Maker unknown

Corpus Christi and Lubbock, Texas

1931-1932

Collection of the Winedale Museum, Kathleen H. McCrady Quilt History Collection acc.#W2h93.06

Signature quilts remained popular. The seamstresses here used an old pattern with new prints, some more colorfast than others. These multicolored dress prints were considered modern and up-to-date.

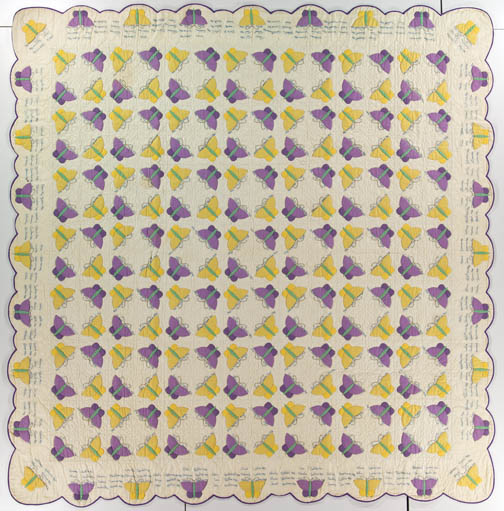

Butterfly

Annie Bell

Johnston County, North Carolina

1937

Private Collection

Family members recalled this quilt being made in 1937. When we look at the fabrics we might guess they are recycled feedsacks but it is important to remember that die-cut packages of butterflies, rabbits and flowers were sold to quilters.

Methodist Aid Society Signature Quilt

Made for Dr. B. I. Mills

Maywood, Nebraska

1940

Collection of the International Quilt Study Center acc.#2002.003.0001

Pastel solid fabrics were popular in new dyes and new shades after 1925.

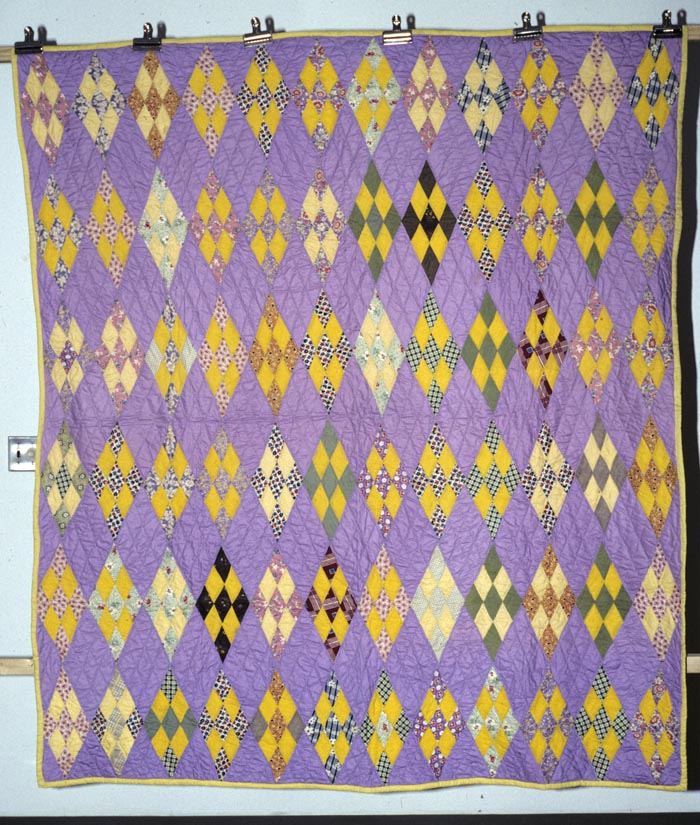

Diamond Nine Patch

Louella O. McClanahan

Putnam County, West Virginia

Dated 1928

Private Collection

Signed and dated, L.O.M. / 1928. The family history recalls that Louella made this scrappy quilt when she was ten years old.

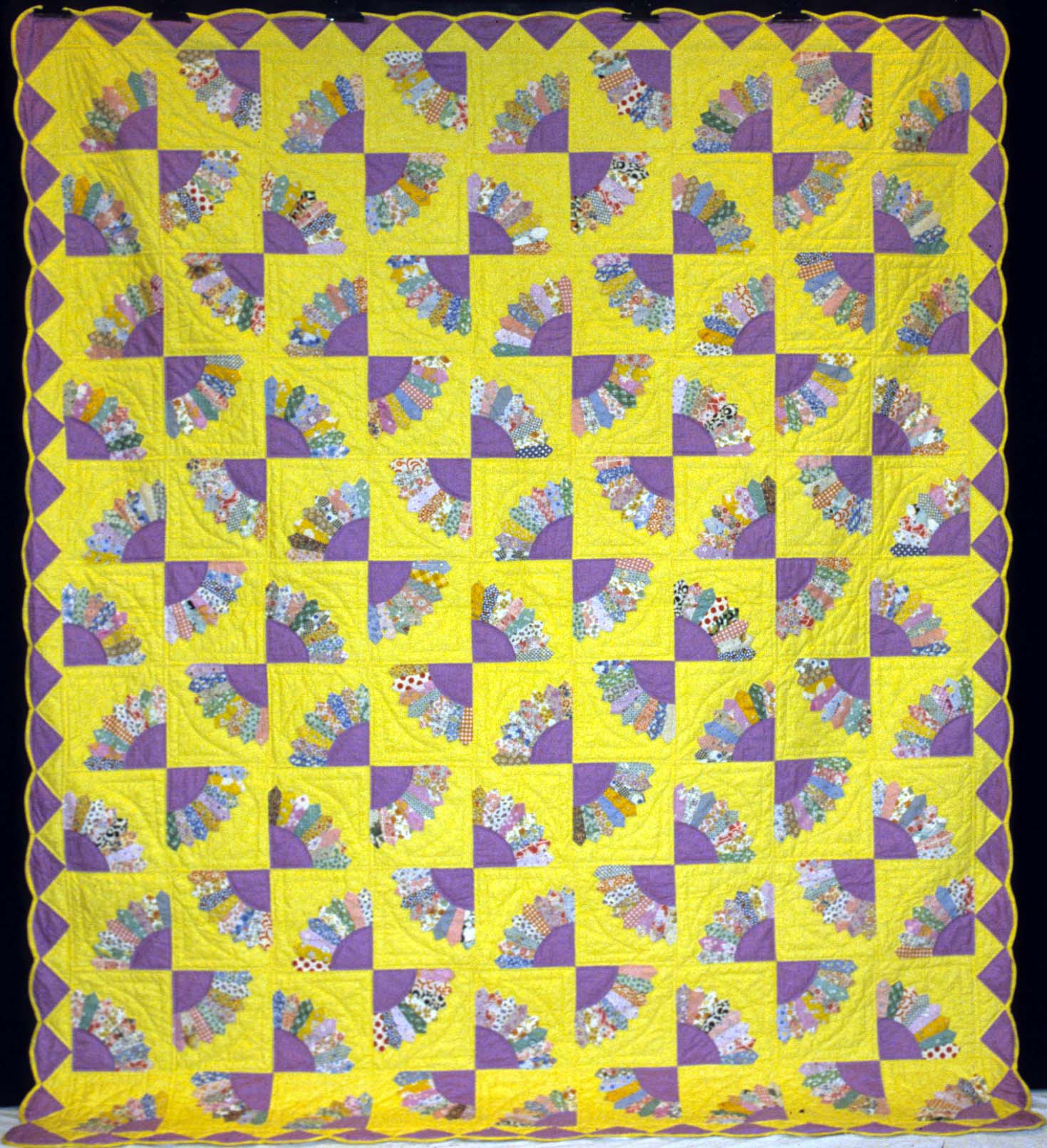

Japanese Fan

Frances L. Harman

Harland County, Nebraska

Estimated date: 1932-1976

Private Collection

Frances used a pattern from the popular rural periodical Capper's Weekly. Japanese Fan with a scalloped border was published in 1932. The top was quilted in 1976. Hundreds of periodicals carried quilt patterns and ads for mail-order patterns.

Barbara Brackman

2011

All rights reserved

-

Documentation Project

Nebraska Quilt Project University of Nebraska-Lincoln

-

Museum

DAR Museum DAR Museum

-

Documentation Project

North Carolina Quilt Project North Carolina Museum of History

-

Documentation Project

The West Virginia Heritage Quilt Search West Virginia Department of Archives and History

-

Documentation Project

Signature Quilt Pilot Project Michigan State University

-

Museum

Winedale Quilt Collection University of Texas at Austin, Briscoe Center for American History

-

Ephemera

Womenfolk 08. Depression Era Quilts: C...

Breneman, Judy Anne

-

Ephemera

Womenfolk 31. Feed Sacks Used for Quil...

Breneman, Judy Anne

-

1932

Double Wedding Ri... Cooper, Rebecca M. ...

-

1932

Dogwood -

1930-1949

Pieced Friendship... -

1930-1949

Butterfly Appliqu... Bell, Annie

-

1930-1949

Methodist Aid Soc... Mrs. Joseph Perkin

-

1901-1929

MC CLANAHAN MCCLANAHAN, LOUELL...

-

1976

Japanese Fan Waldo, Frances L. H...

Load More