BACK TO EXHIBITS

Redwork: A Textile Tradition in America

Redwork: A Textile Tradition in America, January 28, 2007 - January 2, 2008 at the Michigan State University Museum

Introduction

Redwork, a style of "art needlework," first became popular in the United States in the late part of the nineteenth century. This essay explores the reasons why this style of needlework has been popular and the range of objects that have been made in this style. The exhibition draws heavily on objects, ephemera, and archival material from the Michigan State University Museum collections, in particular, the Deborah Harding Redwork Collection.

What is Redwork?

Redwork is a style of decorative needlework that consists of embroidering the outline of designs onto a white or off-white background with a contrasting color thread. This simple, yet striking style is called Redwork for several reasons. Red thread is typically used in this style because the red color contrasts well against a light background; also, during the nineteenth century when the style first became popular, artists could obtain a red thread that was "colorfast," meaning that the red coloring would not wash out or "bleed" onto the white fabric.

Redwork includes many different types of textiles and particularly quilts, clothing, and household items. While Redwork was especially popular during the late nineteenth century in America, artists around the world have continued to make it. Today, artists of Redwork even have websites, blogs, and listservs.

What is "Turkey Red"?

"Turkey Red" is the name of a natural dye used to color fabric. It was thought to have originated in India then spread through the Middle East where it obtained its popular name. Dye masters used the root of the Madder plant to create the red dye that, when used to color fabrics, did not fade or "bleed" onto other fabrics when they were washed. By the mid-nineteenth century, both Turkey Red dyed thread and the dye itself were available in North America. Synthetic dyes became available around 1875 and provided a wider range of red colors but thread or fabric dyed in these synthetic dyes often faded to a rose or even brownish red. The Turkey Red dye typically cost more than other dyes but its durability was highly valued.

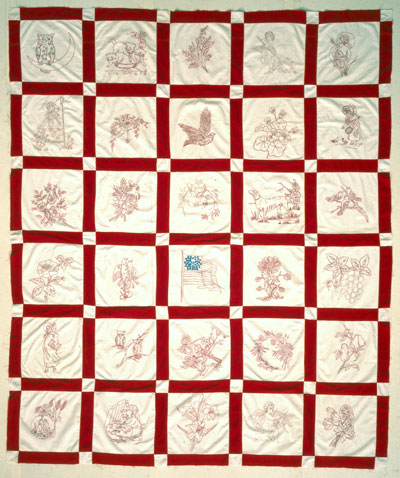

Blue Stars Flag Quilt Top

Maker unknown

c1890

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.3

The “Blue Stars Flag” quilt top is named for the embroidered flag found near the center of the quilt. The flag’s design of forty-one small stars grouped around a larger star is symbolic of Montana’s admission to the United States as the forty-first state on November 8, 1889. This was the Union’s official flag for only three days, as the state of Washington was admitted on November 11, 1889.

Due to its short duration as the nation’s official flag, it is doubtful a commercial pattern was distributed for the flag pattern. An examination of the block reveals a row of pinhole-sized dots, indicating a perforated pattern was used to transfer the design to the fabric. To create the design, a different flag design may have been adapted, or the design may have been copied from a newspaper or illustrated circular.

Although little is known about this quilt’s origin, it is possible that the flag is a clue that the quilt was made in Montana or that the quiltmaker lived there at one time.

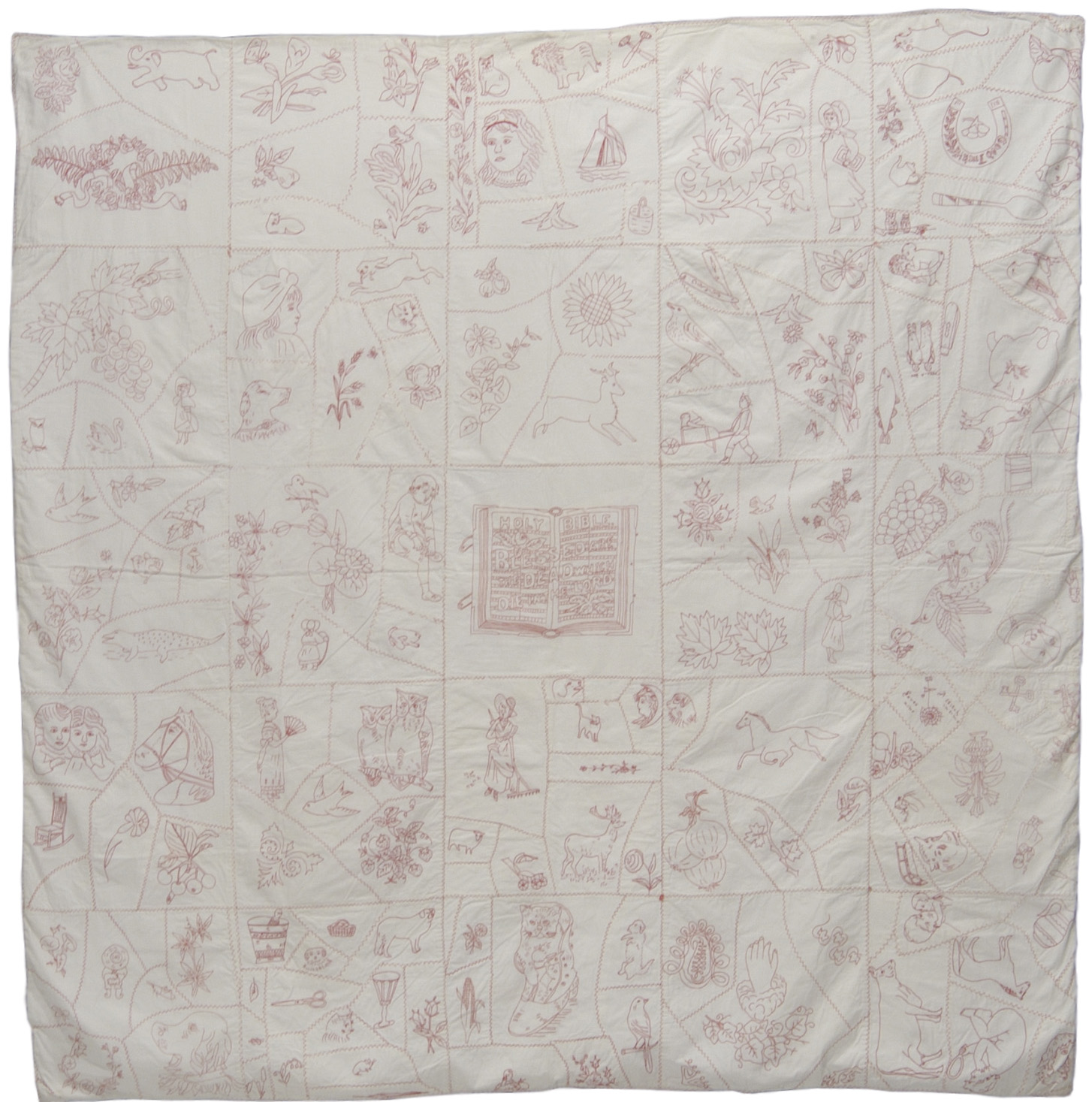

Holy Bible Coverlet

Maker unknown

c1892-1895

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.4

The format of the “Holy Bible Coverlet” mimics a Crazy quilt, a style popular during the same period as Redwork. A Herringbone stitch, know during the late nineteenth century as a Featherstitch, creates the appearance of individual sections, thus creating the look of a Crazy quilt. In contrast to Redwork quilts that utilized one color, one fabric, and only a few stitches, Crazy quilts typically showcased a variety of decorative stitches on a range of fabrics including silks, satins, and velvets.

Rendered on the Bible in the quilt’s center is a passage from Revelations 14:13: “Blessed Art the Dead, Which Die in the Lord.” Does this passage imply the quilt was made as a memory quilt honoring someone who had died? An examination of the images depicted offer clues, but the quilt’s provenance is not known.

Several of the quilt’s embroidered designs reflect the ingenuity of its maker who used images found in advertisements for products such as Cuticura Soap, Imperial Grahnum, and Cod Liver Oil and probably tracings of items such as a teaspoon, keys, or a Bible.

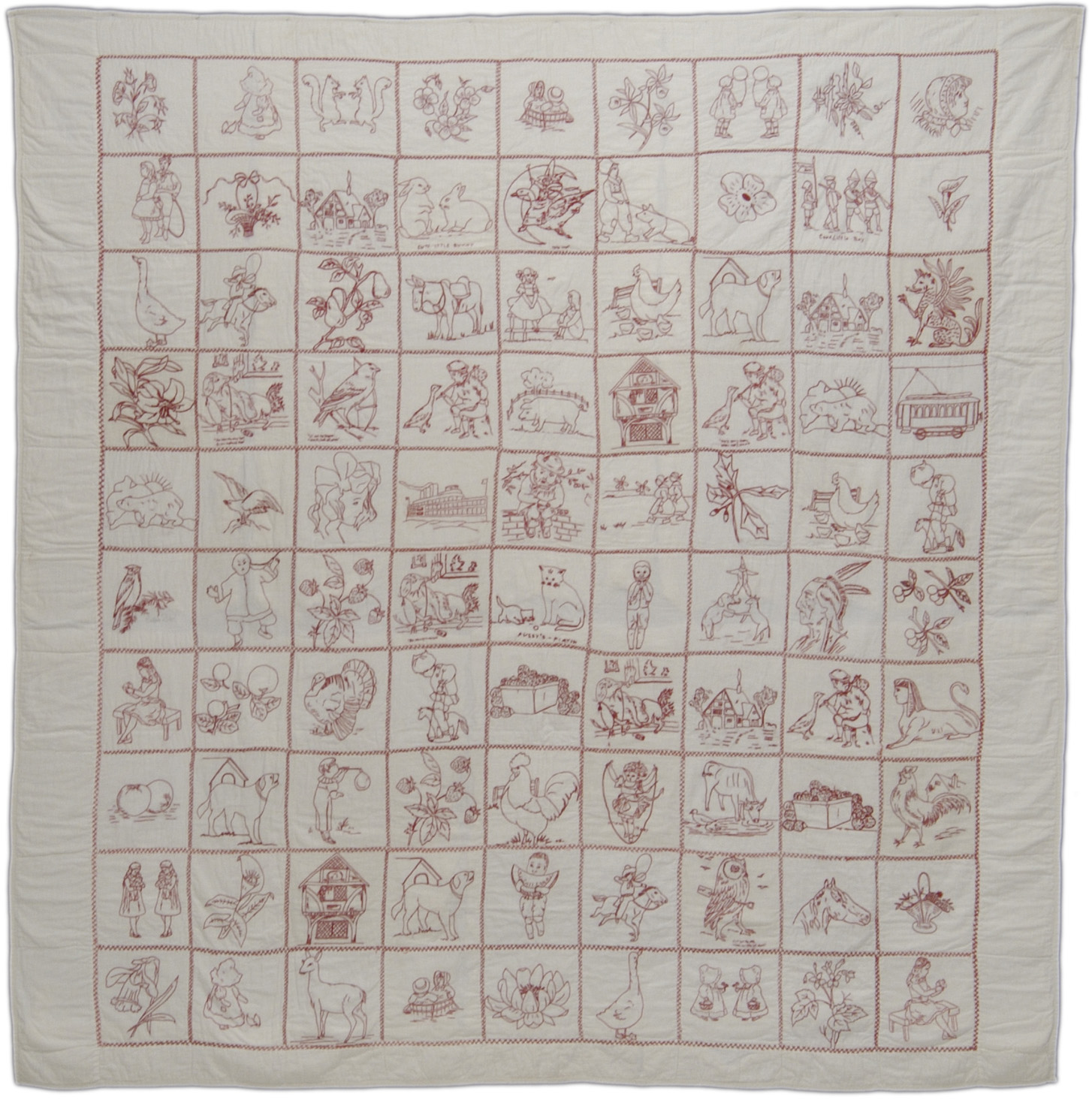

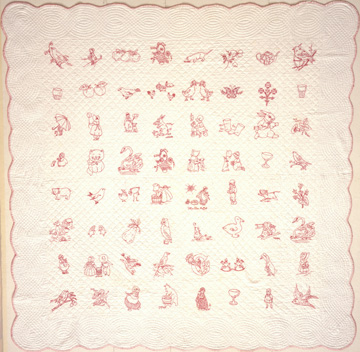

Nursery Rhyme Quilt

Maker unknown

c1910

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.7

The “Nursery Rhyme Quilt” may have been embroidered by several different people, possibly children. It is not uncommon for Redwork blocks to have been stitched by children. The simple stitches used in Redwork could teach embroidery skills and many of the whimsical designs found in Redwork would have appealed to children.

Representations from a number of nursery rhymes included on this quilt are Goosey Goosey Gander, Who Killed Cock Robin?, Old Mother Hubbard, Humpty Dumpty, and Mother Goose. A number of companies offered perforated patterns and stamped linens in sets advertised as Mother Goose or Nursery Rhymes.

An intriguing design found on the quilt is the boat located in the quilt’s fifth row. It is a depiction of the Hudson River Day Lines’ Henrick Hudson. The embroidered design may have been a penny square sold in souvenir shops at the pier or distributed to commemorate the boat’s maiden voyage in 1906.

The Deborah Harding Collection

Deborah Harding, a textile historian, became interested in researching Redwork when she came across a Redwork quilt at a New York City flea market. Her subsequent extensive inquiry into the origins of this textile style resulted in Red & White: American Redwork Quilts and Patterns (2000), the first major monograph on the topic. In 2001, Michigan State University Museum acquired her research collection which included notes, photographs, ephemera and examples of Redwork, including twelve quilts. These materials, added to the Museum's existing collection of Redwork and the subsequent pieces that Harding has donated, form a rich body of primary materials for many research projects.

Sunbonnets

Maker unknown

c1912-1922

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.9

Sunbonnet girls, characterized by the shape of their large, obscuring bonnets, populate this quilt. The girls are seen at work and play in blocks marking the day, the month, and the season and the scenes are adapted from illustrations by Bernhart Wall, whose work appeared on postcards and in children's schoolbooks. Wall's figures can be identified by a distinctive flounce on the girls' bonnets near the back of the neck. Wall produced days-of-the-week and months-of-the-year card series for Ullman Manufacturing Company in 1905 and in 1907 his designs were featured in the book Little Susie Sunbonnet and How Her Year Was Spent, A Story for Little Tots by Uncle Milton.

Little Miss Muffet

Maker unknown

c1921-1923

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.11

The “Little Miss Muffet” quilt may have been made either by or for children. It features an array of motifs whose subjects would appeal to children, including animals and nursery rhyme characters. The term “kindergarten blocks” is used to describe this type of outline work—Redwork designs appealing to children that were stitched by children as young as six or seven.

Several of the blocks in this quilt are done in cross-stitch, one of the first styles of stitches a beginner learned. Several of the figures are small in scale indicating they could have been taken from patterns for children’s clothing and accessories. Six of the designs in this quilt appeared in the 1920 editorial, “Simple Designs That Little Miss Can Embroider or Paint.”

Mikado Quilt

Maker unknown

c1890

Possibly made in Pennsylvania

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.2

Japanese-inspired designs became increasingly popular in America after the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition where more than nine million people were reported to have visited the Japanese pavilion. A variety of Asian-inspired motifs became popular in American art, including cranes, kimono clad figures, fans, teacups, vases, bowls, paper lanterns, spiders in webs, apple blossoms, and chrysanthemums. The Mikado, a comic opera by Gilbert and Sullivan set in Japan, debuted to amazing success in 1885. By May 1886, patterns inspired by the Mikado began appearing in Godey’s Ladies Book and soon after, Mikado patterns were offered by a number of magazines.

Decorative Art Needlework

Plain needlework refers to textiles that have no decoration and are usually made simply for utilitarian purposes. Decorative art needlework refers to textiles that have designs or patterns and can be used for utilitarian purposes but are more often made solely for decorations on clothes or to decorate homes and religious settings. Many sewing techniques are used in making decorative needlework.

Although textile artists around the world have long decorated their needlework, making textiles solely for decorations became especially popular in the United States during the late nineteenth century. Redwork, one style of decorative needlework, first reached its peak of popularity-- especially in the United States--between 1888 and 1925 and it is now popular again.

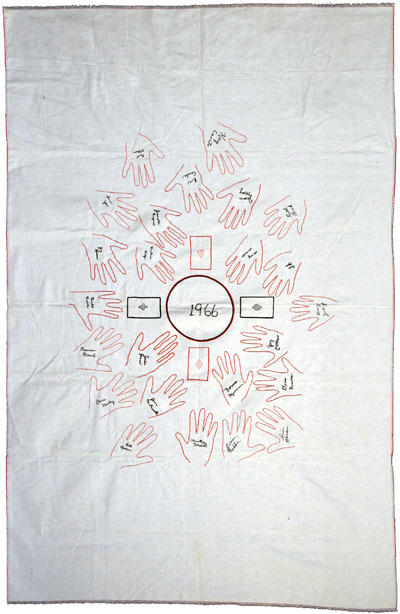

Card Table Cover

Friends of Minnie Dewhurst

1966

Redford, Wayne County, Michigan

Private Collection

When Minnie Dewhurst moved back to her home state of New Jersey, the friends she had made while living in Michigan made her this card tablecloth. Each person traced her hand and then signed her name.

Nightgown

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#1590.29

Decorative Art Needlework and the 1876 Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia

Before the advent of the Internet and satellite communications, fairs, festivals, and expositions were major events where showcases of arts, cultural history, and inventions from around the world were seen by thousands, even millions of visitors. The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia was seen by over nine million visitors and two of its exhibits had profound influences on styles and fashion in the United States. The Japanese Pavilion hosted the most extensive showing of Japanese art the Western world had ever seen and, soon after, American art and design reflected Japanese motifs. The Royal School of Art Needlework from Kensington, England showcased ornamental needlework made by students at the school. Inspired by this exhibit, American Candace Wheeler formed the New York Society of Decorative Arts, which similar to its English counterpart, provided art training to increase women's employment opportunities. Soon new decorative art schools and societies across the country were offering instruction in an array of decorative arts and new art journals provided information and instructions.

Apron

Maker unknown

c1910

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.27

The Redwork designs on this apron may have originally been a pattern intended for drapery.

Good Night Pillow Sham

Maker unknown

c1880

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2004:157.6

Good Morning Pillow Sham

Maker unknown

c1880

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2004:157.7

Decorative Art Needlework and the Artistic Movements

The Aesthetic movement of the late nineteenth century, associated with the work of James McNeill Whistler and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, developed a cult of beauty promoting "art for art's sake." The influence of the Aesthetic movement affected literature, fine art, and interior design in Europe and the United States. The Arts and Crafts movement, originating in England and reflecting the thinking of John Ruskin and William Morris, celebrated design and craftsmanship. Included was the concept that a beautiful home was believed to reflect the morality and productivity of its inhabitants.

The effects of both artistic movements impacted decorative arts, including art needlework, as a craze spread across America during the late nineteenth century to embellish all sorts of household textiles.

Pillow Sham

Maker unknown

c1880

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2004:157.1

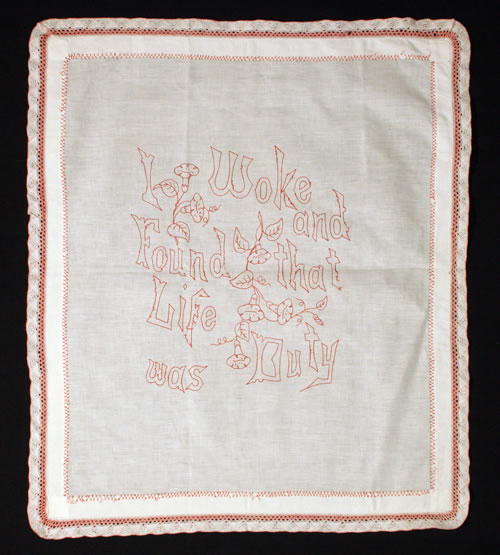

I Slept and Dreamed that Life was Beauty

Pillow Sham

Maker unknown

c1880

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2004:157.2

I Woke and Found that Life was Duty

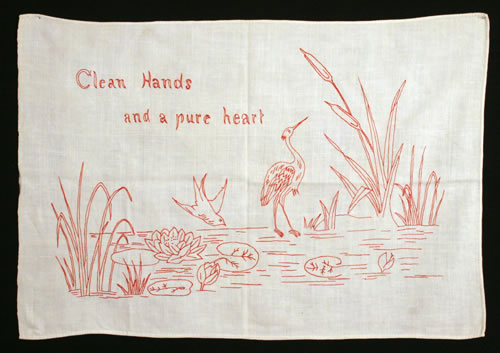

"Clean Hands and a Pure Heart" Splasher

Maker unknown

c1900

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.14

Water-related motifs, such as swans, cranes, cattails, frogs, lily pads, or children engaging in activities like boating, fishing, or swimming were usually intended to be used on splashers.

Marketing Redwork

During the 1880s, Redwork supplies became accessible across the nation. Widely distributed American women's magazines such as The Ladies' Home Journal and Godey's Lady's Book published embroidery patterns, listed advertisements for patterns, and offered patterns and Redwork stamping kits as premiums for subscribers. Newspapers and journals also carried advertisements for pattern companies, thread manufacturers, needlework products and local sources for these items.

Supplies could be purchased through the mail or at local department stores, fabric stores (called "dry goods stores"), or even at small businesses specializing in Redwork. Some of these outlets also offered customized patterns for their customers. Today, Redwork designs can also be obtained through the Internet.

Tea Towel

Maker unknown

c1910

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.19

Redwork Embroidered Wall Hanging

Maker unknown

c1880

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.26

Redwork Embroidered Damask Tray Cloth

Maker unknown

c1910

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.24

Redwork as Income

Redwork demands skill in stamping (transferring designs onto fabric) and in embroidery (stitching the designs). Both embroidery and stamping for others became a way for individuals, usually women, to earn money in the home. Stamping pattern companies even recruited women to become professional stampers.

Most Redwork embroidery was done by the person who purchased a stamped design but in some cases, particularly in items produced as fundraisers, a talented embroiderer was recruited to do the needlework.

Cloth or Curtain

Maker unknown

c1910

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.23

"Sit Thee Down" Chair Back

Maker unknown

c1886

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.15

Depictions of chairs were designed to be stitched onto tidies for chair backs

Doily

Maker unknown

c1900

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.1

Redwork: Design Types, Designers, Sources, and Influences

Designs used by needlework artists in Redwork are varied and reflect individual interests and creativity as well as social, political, and artistic influences. Many designs were of images or motifs thought to be closely associated with woman's domestic experiences: children, animals, birds, flowers, nursery rhymes, characters from children's fiction, household items, women's hairstyles, and fashion accessories such as fans or purses. Redwork designs were also made to commemorate significant events or important elements of popular culture in our nation's history, such as the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

Certain designs were intended to be used on particular types of textiles. For instance, designs with the phrases "Good Morning" and "Good Night" were intended as pillow shams. By the early twentieth century a number of Redwork designs were developed and marketed specifically for use on quilt blocks.

Most designs and motifs used in Redwork were professionally drawn by illustrators and then commercially distributed. Although most designers were anonymous, two were well known. Artist Kate Greenaway was known for her drawings of children and flowers and Ruby McKim, for her designs often used for quilt blocks.

Redwork stitchers also created their own patterns. Their designs were often inspired by fashion illustrations, children's books, advertisements, political cartoons, teacher manuals, and wallpaper designs.

The designs used on a particular textile are important clues to dating the work, because many designs can be traced to specific manufacturers or relate to specific events in history.

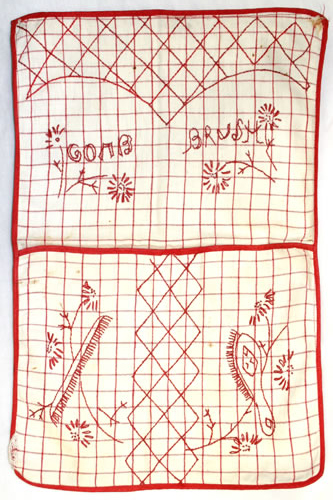

Reversible Laundry Bag

Maker unknown

c1888

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.17

Pocketed Comb and Brush Case

Maker unknown

c1900

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.21

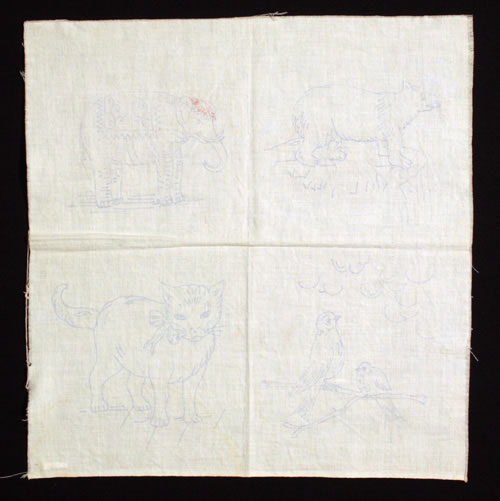

Unfinished Quilt Blocks

Maker unknown

c1900

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2001:160.34

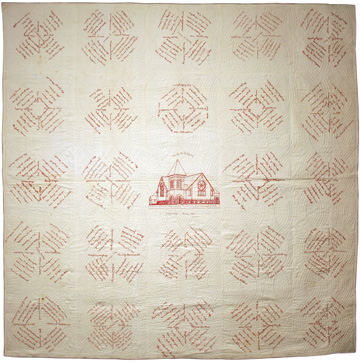

Redwork and Fundraising Quilts

A strong and longstanding quilt tradition is the use, especially by women, of quilts to raise money for a wide variety of causes. Individuals and organizations have made thousands of dollars by making and selling, raffling, and auctioning off quilts. A particularly effective means of raising funds is through the making of subscription quilts, a form in which individuals, businesses, and organizations pay a small amount of money for the privilege of having their name inscribed on a quilt in support of a particular local, national, or even international cause. When other avenues to engage in support for these causes were denied women, making subscription quilts proved an effective tool to demonstrate their convictions and to channel skills and energies that would make a difference in the causes they believed in.

Names on subscription quilts were often done in Redwork. Because their primary purpose was to raise funds, the design and construction of subscription quilts were generally, though not always, simple. Many of these forms of quilts show little or no wear and are still extant in good condition, partially because these quilts were designed to be used as fundraisers and only incidentally, if at all, as bedcoverings, and partially because subscription quilts have been kept by organizations and individuals as documents of history. Many have been recorded in state and regional quilt documentation projects.

Ishpeming Fundraising Quilt

Maker unknown

1903

Ishpeming, Michigan

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2006:128.1

This quilt includes the names of more than 400 church members who contributed money to the First Methodist Episcopal Church of Ishpeming, Michigan. The names are placed around a center block commemorating the congregation’s newly built church building. The majority of surnames are Cornish, reflecting one of the ethnic groups represented in the mining population of Michigan’s western Upper Peninsula.

The Methodist Episcopal Society of Ishpeming, Michigan held their services in a schoolhouse from 1867 until their first church was built in 1869. A foundation for a new church was laid in 1891 on North Third Street, but economic conditions and labor problems halted the project, and instead Ishpeming Greenhouses was eventually constructed on the foundation. Later, a new church was built on the site of the original church at Division and Second streets. The new church was completed in 1903 and was known as the First Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1955, the church was renamed Wesley Methodist Church following a merger with another congregation. The church building depicted on the quilt was razed in 1972 following a fire. Wesley Methodist Church can currently be found on Hemlock Street in Ishpeming.

Ku Klux Klan Quilt (Shoo-Fly Variation)

Made by various individuals

1926

Chicora, Michigan

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2000:71.1

In 1987, Loma Bell Rowe Mudget gave away some of her belongings to family members. She knew that her nephew Karl, a high school teacher, was interested in family and local history and presented him with a bag, inside of which were two items Karl had never seen before: a family bible and the K.K.K. quilt. Loma told Karl that she had inherited the quilt from her father, also Karl's grandfather, Frank, when he had died in 1960. As an educator and historian, Karl was determined to find out more about it. Karl brought the quilt to the attention of historians specializing in state and local history and importantly, Karl interviewed elder family members about the quilt.

Karl discovered that his paternal aunt, Grace Rowe Way, at age sixteen, had been enlisted, much to her embarrassment but because she had fine handwriting and sewing skills, to stitch names onto the quilt. Way recalled that each person paid 10 cents to have their name stitched on a block and when the quilt was completed, members of the local Klan entered a raffle to win it. Karl's grandfather, Frank Rowe, held the winning ticket.

The K.K.K. Fundraising Quilt: A Primary Resource for Research and Education

This quilt, done in the Redwork style, is a significant example of how textiles are important documents of history and how objects of material culture provide primary source data for describing, analyzing, and understanding aspects of human history. The materials, construction, design, pictorial imagery, signatures, the oral histories and related ephemera, and even condition of this quilt hold clues that strengthen and expand our understanding of quiltmaking, of Klan activity, and of the social and cultural history of a particular community at a particular point in time.

Whether or not they intended to do so, members and supporters of the Ku Klux Klan in one Michigan community created--in this Redwork textile--an artifact that continues to be a testimony to their beliefs, relationships, and actions. In an age where we continue to struggle with local, national, and global issues of tolerance, social justice, and human rights, this artifact.

Redwork: Techniques of Transferring Designs to Fabric

Redwork decoration on fabric is done by embroidering (or sewing stitches) over a design that has been directly drawn onto fabric or a design that has been transferred to the fabric from another source. Several methods can be used to transfer a design.

Perforated paper technique: Designs are printed or drawn on thick, stiff paper and then small holes are pricked along the pattern lines to create a perforated pattern. A powder is rubbed over the holes which results in small dots in the same design on the fabric. Perforated patterns could be purchased or made at home and could be used multiple times. Stamping kits-- including a box of dark powder, one of light powder, and devices known as pounces to distribute the powder were widely advertised in women's magazines for purchase or as premiums. As an alternative to powders, stamping ink, sometimes in the form of wax cakes, could be used with perforated patterns.

Iron-on transfer technique: A hot iron is pressed against the back of a pattern sheet. The iron's heat transfers the design to the fabric.

Carbon paper transfer technique: Carbon paper or tracing paper is placed between the design and the fabric. Tracing the design transfers it to the fabric.

As the popularity of Redwork grew, pre-stamped fabric, sometimes known as "Penny Squares," became available. Today, designs can be printed directly onto fabric using a computer and printer.

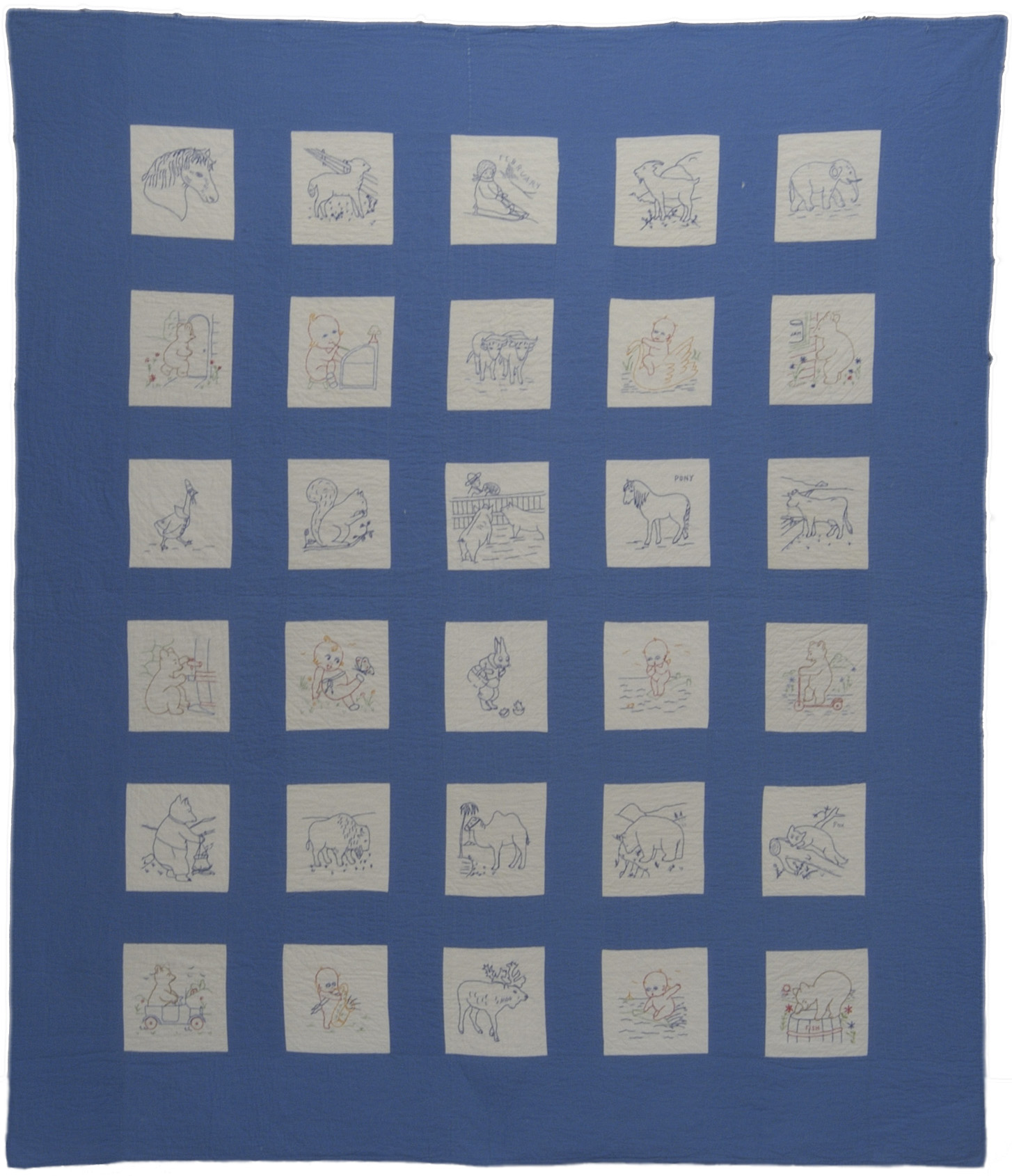

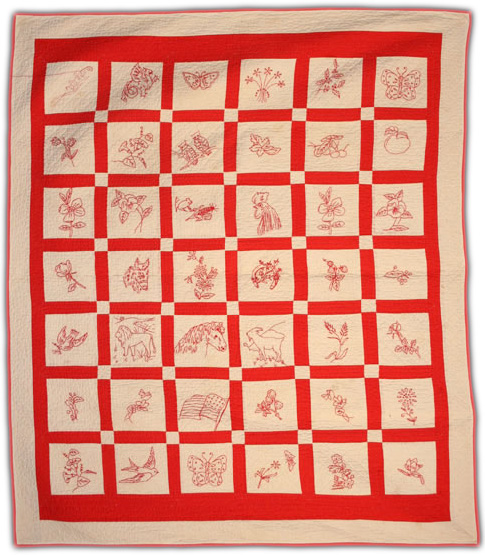

Boy's Quilt

Emilie Ann Clarke

D1924-1935

Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#6119.12

The Clarke Family quilt collection, given to Michigan State University Museum in 1986 by Dr. Harriet A. Clarke and her brother, George M. Clarke, includes forty-five quilts and quilt tops completed between 1926 and 1946 by Bozena Vilhemina Clarke, her daughter Laura May Clarke, and daughter-in-law Emilie Ann Clarke. The collection also includes numerous hand-made templates and patterns, unique hand-colored graphs of planned quilts, newspaper and magazine clippings, and personal inventory notes written by the quilters. Because the Clarke quilt collection represents virtually the entire output of quilts made by one family over a 20-year period and the supplemental materials reflect the entire quiltmaking process from inception to completion, it offers a unique glimpse into the quilting lives of one family. The collection also provides an excellent study example for understanding quilting activity in Detroit during this period and the relationship of the Clarke family quilters to the regional and national rejuvenation of interest in quiltmaking and home arts of the 1920s to the 1940s.

For a pair of children’s quilts, Emilie Clark pieced together squares featuring outline embroidered pictorial images. This quilt, known by the family as the “Boy’s Quilt,” features designs rendered mostly in blue embroidery floss. After World War I, colorfast cotton embroidery threads became available in a variety of colors. As other dye colors became more stable, outline in other colors became increasingly popular. Post-1910, bluework, or all blue embroidery designs, became more common. Emilie completed a companion quilt, known as “Girl’s Quilt” whose designs include florals, “kewpies,” and sunbonnet figures.

Redwork Quilt

Metta V. Rybolt with secondary embroidery by Betty MacDowell

1950

Lapeer, Michigan

Private Collection

Metta, an avid quiltmaker, made this quilt for her new great-granddaughter Marsha MacDowell who slept under the quilt when she was a young girl. The quilt thus became quite worn and much of the embroidered was worn off. As a gift to Marsha for her twenty-fifth birthday, Marsha's mother Betty re-embroidered all of the squares except one which she left partially finished with a threaded needle. She thought this would help Marsha appreciate the work involved and she would complete the restoration.

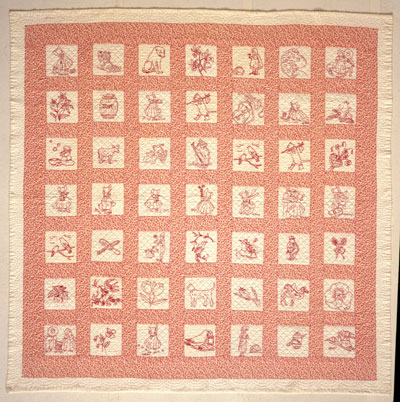

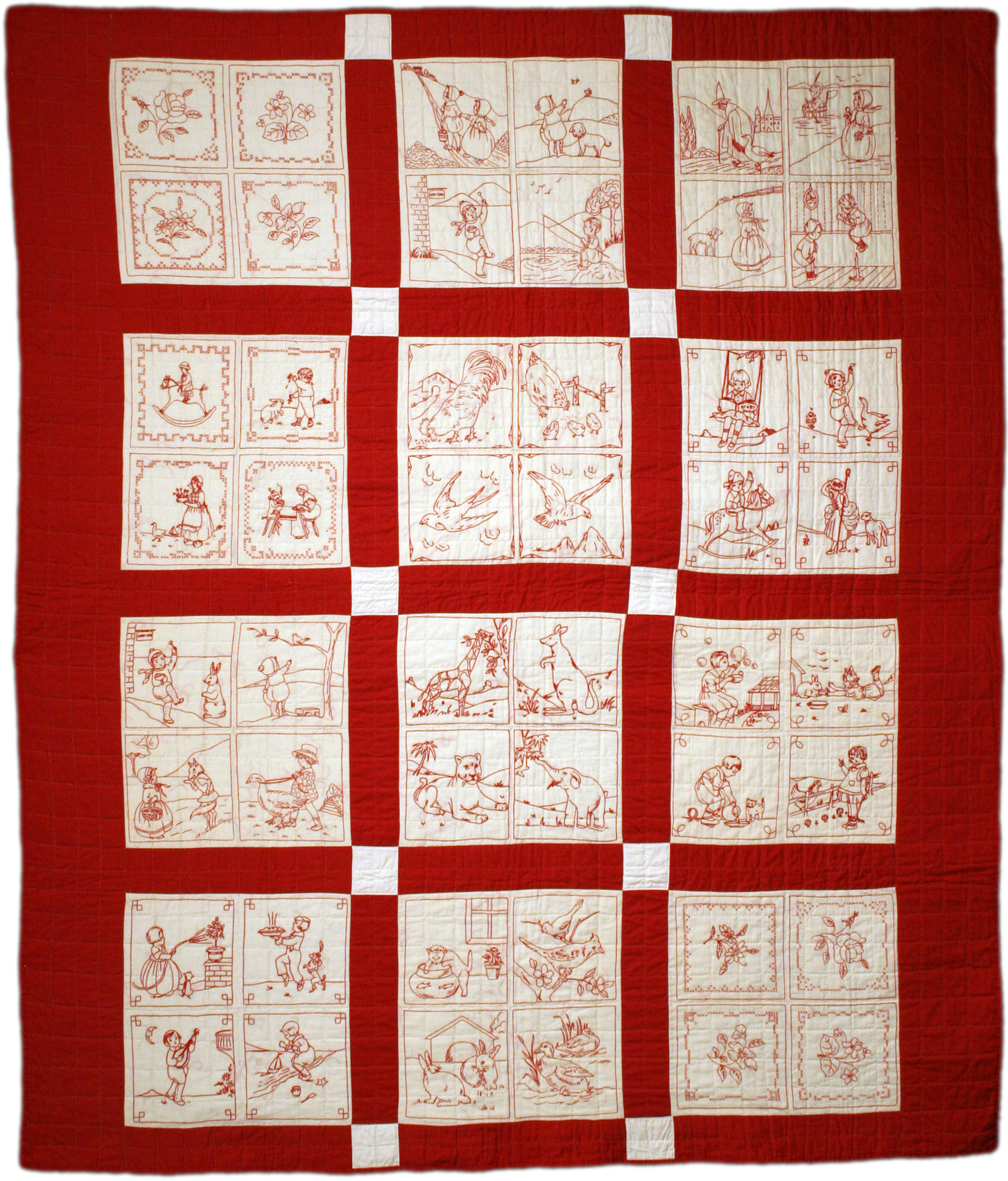

Redwork

Betty Quarton Hoard and Winnie Quarton

c1929

Birmingham, Oakland County, Michigan

Collection of the Michigan State University Museum acc.#2006:142.1

The Durkee-Blakeslee-Quarton-Hoard Collection consists of quilts representing four generations of women from Oakland County, Michigan. Concern that family pets might damage a collection of pristine family quilts prompted Betty Quarton Hoard to donate seventeen quilts made by her grandmother, Martha L. Durkee Blakeslee, great-grandmother, Mary Elizabeth Beardslee Durkee, and mother, Emma Blakeslee Quarton, to the Michigan State University Museum. Following Betty's death in 2005, her family donated an additional three quilts, including this quilt made by Betty and her sister Winnie.

Oakland County, Michigan has been home to members of the family, since 1823 when Betty's forebear Wilkes Durkee moved from Cayuga County, New York to the town of Franklin. Betty's grandfather, Frank Blakeslee, owned a dry goods store in Birmingham, the city in which resided. Betty recalled that the boxes of fabric, lace, and other notions that were available from the family's store always provided her with scraps from which to make doll clothes. Ownership of the store undoubtedly contributed to the eclectic variety of fabric found throughout the family's quilts.

Betty's own quilting began with this detailed Redwork piece created with her sister, Winnie. The project commenced when Betty was about fourteen, an age she thought was too old for this task and thus she only completed around four of the blocks. Winnie finished the remainder. The motifs embroidered on blocks set with a red sashing include numerous depictions of nursery rhymes and fairy tales.

Glossary of Needlework Terms

• Batting - The middle layer of a quilt that provides padding and warmth.

• Blanket or Buttonhole Stitch - A stitch sometimes used around the edges of a finished Redwork quilt or coverlet.

• Featherstitch - A rounded, looped stitch used to cover joined seams (the point where two pieces of fabric are stitched together). During the late nineteenth century, the term Featherstitch was also used to describe a Herringbone Stitch.

• Herringbone Stitch - A stitch comprised of crossed lines sometimes used to cover joined seams.

• Muslin - A plain woven cotton fabric in a natural or bleached white color.

• Penny Square - Muslin squares with stamped designs. Penny squares could be purchased for a penny at local department or fabric stores.

• Splasher - A textile hung behind a washstand or sink to prevent walls from being splashed with water.

• Stamping - A technique used to transfer Redwork designs to fabric.

• Stamping Outfit - A craft kit that was sold to needleworkers. The kit included patterns, instructions, and supplies to transfer designs onto cloth in preparation for embroidery.

• Stem Stitch - The basic stitch used in Redwork. It is a ropelike stitch that forms an unbroken line, giving the effect that the image has been sketched onto the fabric. A Stem Stitch is similar to an Outline Stitch.

• Summer Spread - A single layer coverlet with finished edges or a lined coverlet that contains no batting.

• Tidy - A textile used to protect the back, arms, or headrest of a chair or sofa from wear and soil.

• Tied - A technique used to hold the layers of a quilt together using tied knots rather than quilting stitches.

Resources

The Deborah Harding Redwork Collection at the Michigan State University Museum, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan

American Quilts from Michigan State University Museum, Marsha MacDowell, ed., Tokyo, Japan: Kokusai Art, 2003. Red & White: American Redwork Quilts, Deborah Harding, New York: Rizzoli, 2000.

Credits

Project Coordinator and Curator: Mary Worrall, Michigan State University Museum

Curatorial Assistance: Marsha MacDowell, Michigan State University Museum

Research Consultant: Deborah Harding

Collections Manager: Lynne Swanson, Michigan State University Museum

Quilt Collections Assistant: Beth Donaldson, Michigan State University Museum

Photography and Digitization: Pearl Yee Wong, Michigan State University Museum

Virtual Exhibit: Mary Worrall, Michigan State University Museum, Justine Richardson, MATRIX: The Center for Humane Arts, Letters, and Social Sciences and MATRIX: The Center for Humane Arts, Letters, and Social Sciences Online at Michigan State University

Exhibit Design and Installation: Juan Alvarez, Michigan State University Museum

Graphic Design: Melinda Hamilton, Michigan State University Museum

Public Relations: Lora Helou, Michigan State University Museum

Public Relations Assistant: Julia Meade

Michigan State University Museum Museum Director: C. Kurt Dewhurst

The exhibition is supported in part by funds from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, MSUM Traveling Exhibition Endowment, and Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs with additional support from Michigan State University Museum and MATRIX: The Center for Humane Arts, Letters, and Social Sciences Online at Michigan State University.

-

Museum

Michigan State University Museum Michigan Quilt Project

-

Documentation Project

Michigan Quilt Project Michigan State University

-

Ephemera

Analysis of a Late Nineteenth-Century ...

Shultis, Lynne

-

Ephemera

Womenfolk 20. Redwork Embroidery Histo...

Breneman, Judy Anne

-

Collection

Deborah Harding Redwork Collection

Worrall, Mary

-

Ephemera

Womenfolk 07. Victorian Era Quilts fro...

Breneman, Judy Anne

-

Ephemera

Quilt History Tidbits #30 - Penny Squa...

Quilt History Tidbits

-

Gallery

Signature Quilts 5: Redwork

Alexander, Karen; Hornback, Nancy; McDowell, Marsha; Sikarskie, Amanda Grace

-

Ephemera

Catalogue of Stamping Patterns Embraci...

Farnham, Mrs. T. B.

-

Ephemera

Ingall's Fancy Work Book

Ingalls' Mail Order Business

-

Ephemera

Manual of Needlework

Pattern Publishing Co.

-

c1889

Blue Stars quilt ... -

1895

Holy Bible Coverl... -

c. 1910

Nursery Rhyme Red... -

1922

Sunbonnets -

1923

Little Miss Muffe... -

c.1890

Mikado quilt -

1966

Card Table Cover -

c1910

Apron -

c1880

Good Night Pillow... -

c1880

Good Morning Pill... -

c1880

I Slept and Dream... -

c1880

I Woke and Found ... -

c1900

Clean Hands and a... -

c1910

Tea towl -

c1880

Embroidered wall ... -

c1910

Embroidered Damas... -

c1910

Cloth or curtain -

c1886

Sit Thee Down Cha... -

c1900

Doily -

c1888

Reversible laundr... -

c1900

Pocketed Comb and... -

c1900

Stamped quilt blo... -

1903

Ishpeming Signatu... -

1926

Chicora KKK Quilt... Ku Klux Klan, Chico...

-

1901-1929

Embroidered Squar... Clarke, Emilie Ann

-

Redwork Rybolt, Metta Celes...

-

1929

Redwork Hoard, Betty; Quart...

Load More