BACK TO ESSAYS

Amish and "English": Quilts from the Illinois State Museum

American quilts are remarkable for their variety—achieved through fabrics, techniques, color palettes, formats, and patterns. Available fabrics and popular trends have influenced American quiltmaking, from the first colonial chintz quilts through the commercialization of quiltmaking in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Because the Amish have sought separation from the “English” world in many aspects of their life, it is tempting to assume that their quilts were also made in isolation from larger American trends. This comparative exhibit of Amish and “English” quilts from the Illinois State Museum collection dispels this notion. In Illinois, Amish and “English” quilters were using the same fabrics, techniques, colors, formats, and patterns, with only a few exceptions. The Amish didn’t use print fabrics in quilts made for their own use because of their religious beliefs, and they rarely used appliqué patterns or large amounts of white fabric.

Similarities in the quilts can be expected, since current evidence suggests that the Amish first learned quiltmaking in the 1830s from their “English” neighbors. They were using the same sources for fabrics—local stores, peddlers, and mail-order catalogs. The Amish also learned about quilt patterns through newspapers and magazines popular with farm families, and they saw “English” quilts at county fairs, where quiltmaking competitions exposed them to such new styles as log cabin and crazy quilts. “English” quilters also made quilts using only solid-color fabrics, and examples of this are in this exhibition. Such quilts could be mistaken as Amish, if their histories were not known.

Some differences are subtle. The Illinois Amish tended to prefer simpler pieced patterns and sometimes adapted “English” patterns by enlarging a block pattern or by using fewer but larger pieces. Amish colors were generally darker, even during the pastel trend in the 1920s and ’30s. Sometimes the Amish quilted more complicated patterns, especially feathering. This emphasis on quilting can be seen even in their early handwoven wool quilts. The Amish rarely used silk fabrics when silks were popular among the “English” for crazy quilts and log cabin piecing. The Amish continued to use wool fabrics in their quilts in the early 1900s when “English” quilts were mostly cotton. All of these similar and different characteristics illustrate that both Amish and “English” quilts are part of the diversity that defines American culture.

Who are the Amish?

The Amish are a conservative, pacifist Christian religious group with origins in the Protestant Reformation in sixteenth-century Germany and Switzerland. They were named for their founder, Jacob Ammon. The first Amish people came to Pennsylvania in 1737, seeking religious freedom. As Amish families followed the westward expansion of America, some settled in east central Illinois, near Arthur, in 1865. Religion is integral to all aspects of Amish life, and nonconformity to the secular world around them is symbolic of their devotion. The Amish reject many aspects of modern technology—gas-powered vehicles, telephones, and high-power electricity—that they feel could disrupt the cohesion of the community. Dress is modest and uniform, and only solid-color fabrics are used. Photography of individuals is considered idolatrous. Today the Amish community in Arthur consists of about 4,200 residents.

Who are the “English?”

Because the Amish speak a Germanic dialect among themselves, they refer to all people outside their community as “English.” The term is confusing because the Amish also speak English, and other people with Germanic ethnicity are still considered “English” to the Amish. Non-Amish is a less colorful but more accurate term for “English.” The “English” quilters represented in this exhibit are from many ethnic and religious backgrounds—German, English, Irish, Polish, Cherokee, Methodist, and Jewish—but they were all born in America and are foremost Americans—as are the Amish.

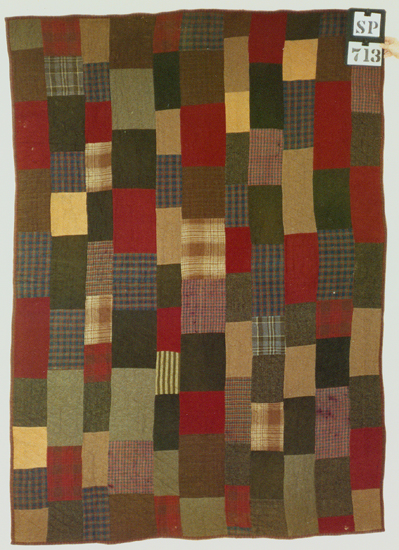

Scrap

Matilda Ann Jones Foster

c1870

Mt. Zion, Macon County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1974.17 (746932)

Scrap Quilt

Magdalena Fisher Yoder

c1875

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.17>/p>

To warm the beds of rural homes, Illinois women often made quilts from scraps of wool left over from making clothing. As with both of these examples, quilters sometimes used handwoven fabrics, as well as early mill-woven fabrics. Spinning and weaving equipment was common in Illinois farm homes as late as the 1870s. Small local woolen mills also served regional needs. The disruption of the cotton trade during the Civil War probably was a large factor in the use of wool fabrics in Illinois at this time. Matilda used many plaid fabrics that were very popular among the “English.” Magdalena’s choice of solid-color fabrics reflects her plainer Amish tastes; however, she added an interesting visual texture to her quilt by using a few pieces of a handwoven alternating-thread-color fabric (red and blue).

These utility quilts were often simply pieced with no particular pattern in mind. Matilda Ann sewed rectangles of similar widths together to make long strips that she then sewed together—no need to match seams. Magdalena chose to work with a 6 ½-inch-square format and to cut her scraps to fit—sometimes piecing smaller squares or rectangles together to make the square and carefully matching the seams when sewing the rows together to form a checkerboard. Although only a few of these utility quilts have survived, the eight in the Illinois State Museum’s collection suggest that it was more common for “English” quilters to use wool batting and for Amish quilters to use cotton. “English” wool utility quilts were commonly stitched with allover patterns of diagonal lines or fans, while the Amish seemed to use a variety of quilting patterns. In the four quilts in the Museum’s collection, Magdalena used alternating bands of designs—a style that seems to be her own.

Matilda Ann and Magdalena were very close in age and lived about 30 miles from each other in central Illinois. Their lifestyles before electricity came to rural Illinois would have been similar; however, Magdalena pieced with a treadle sewing machine, while Matilda Ann pieced by hand. Sewing machines were becoming affordable and available in Illinois during the 1870s, and Magdalena’s quilt was probably made later than Matilda Ann’s. However, “English” quilters in Illinois evidently preferred hand piecing even into the twentieth century.

Nine Patch

Matilda Ann Jones Foster

c1880

Mt. Zion, Macon County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1974-17 (746936)

Nine Patch

Catherine Miller Gingerich

Date

Iowa

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.59

The Nine Patch block is one of the most common and basic pieced blocks used by Amish and “English” quilters alike. Squares, each divided into nine smaller squares, could be sewn together with sashing strips or with alternating unpieced squares, creating an overall pattern that is more geometrically controlled than that of a scrap quilt. Amish and “English” quilters in Illinois worked in both of these sets, or styles, of sewing blocks together.

Both of these wool comforters contain patches of handwoven fabrics and have thick batting. Although the thickness of the batting and fabrics would have made hand quilting difficult, the Amish bed cover was hand quilted, with different patterns in the plain and pieced blocks. The “English” comforter was tied with knots in a regular pattern to keep the layers together. The Amish comforter was also tied with rows of knots of different colored thread in the border, as well as in the center. Layered bed coverings that are tied and not quilted are usually called comforters, or comforts. This Amish bed cover is difficult to categorize. Is it a quilt or a comforter? It may have started out as a quilt, sustained some damage, and was then transformed into a comforter. Dark gray patches have been appliquéd over worn areas of lavender on the top. This repair appears old, as do the tied knots.

The Amish comforter descended in the family of Catherine Miller Gingrich, who they believed made it. No evidence has been found that Catherine ever lived in Illinois; however her aunt, Barbara Miller Yoder, was one of the first women to settle in Illinois in 1865. The distinctive red and blue alternating-thread-color fabric found in this comforter is also found in many of the early Illinois quilts associated with this family. Could Catherine have been inspired to make this comforter after visiting Illinois from her home in Iowa, or could it have been a gift from an Illinois relative? Though many questions remain, the similarities with other Illinois quilts are notable. Matilda, the “English” quilter, also made a scrap quilt in this exhibit. She lived about 30 miles from the Arthur Amish community.

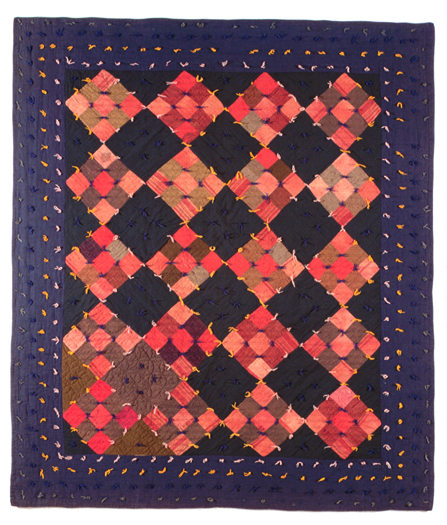

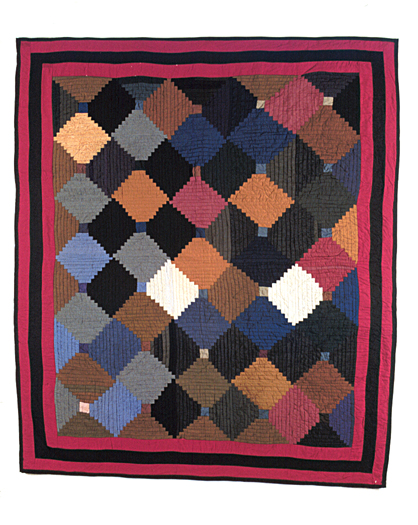

Square on Point

Maker unknown

c1900

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.132

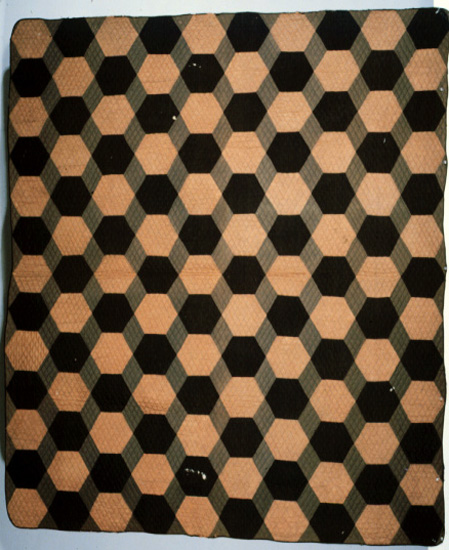

Hexagon and Diamond Mosaic

Sarah Vaughan Black

c1880

Jacksonville, Morgan County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1968-32 (746827)

As the wool industry developed in the late nineteenth century, many specialty fabrics became available in Illinois through dry-goods stores, peddlers, and mail-order catalogs. These fabrics, such as henrietta and cassimere, often used a cotton warp and wool filler yarns and were processed to have a softer hand and to drape better than handwoven and early mill fabrics. Manufacturers developed brilliantine in an attempt to create a dress fabric that looked like silk but was not as expensive. Both of these quilts are made with scraps of brilliantine, a specialty wool with a shiny appearance created by using mohair as the filler yarn. Among the Amish quilts in the Museum’s collection, there are many examples of quilts using brilliantine; however, among the “English” quilts, examples are fewer. Illinois newspaper advertisements indicate its availability in dry-goods stores, where it was also called alpaca. “English” quilters seem to have preferred cotton fabrics for their quilt tops, while the Amish in Illinois were still using wool.

Both of these quilts are made with simple shapes repeated in an allover design. Sarah Vaughn Black used hexagons and diamonds in a limited palette of contrasting colors to create a pattern similar to that of a tile floor. The Amish quilter used simple squares placed diagonally, and added borders and complexity with quilting designs. Her placement of colors is unexpected—but balanced. She may not have had sufficient fabric to create a regular color pattern; however, she did attempt to balance the peach triangles at the right with a narrow inner border of the same color on the left.

Sarah Vaughn Black was born in Kentucky and came to Illinois when she was married in 1853. Sarah’s home in Jacksonville was about 106 miles from the Arthur Amish community; however her quilt shows how similar her fabric and color choices were to Amish aesthetics at this time. Seven of her quilts have been given to the Illinois State Museum. Three are cotton with complicated pieced patterns and intricate quilting. Two are silk crazy quilts, and one other wool quilt is pieced with lightweight wools in a Pineapple Log Cabin pattern.

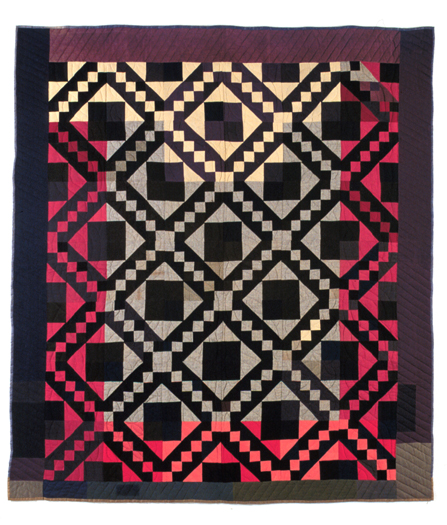

Log Cabin Courthouse Steps

(Mary) Clara Rush Moore

c1910

Arcola, Douglas County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1975.10 (746955)

Log Cabin

Elizabeth Briskey Mast

c1900

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.12

Log Cabin quilts were popular among “English” quilters from the 1870s through the 1910s. The basic block is made by starting with a small square and sewing narrow strips of fabric in sequence around all four sides, enlarging the block as it is “built.” The most commonly used construction method involved adding the strips around adjacent sides of the square with light and dark color strips placed to visually divide the block into half diagonally. A less common method, called Courthouse Steps, involved sewing the strips in sequence on opposite sides of the square. Light colors are placed on opposite sides and dark colors on the other sides, dividing the square into quarters diagonally. Sometimes each quarter is filled with the same fabric or similar fabrics.

These two Illinois quilters used ideas from both Log Cabin techniques to create their similar quilts. They used the basic Log Cabin construction (adding strips to adjacent sides) and Courthouse Steps coloration (with the same fabric in each quarter). To create the effect of squares of color on point, colors on adjacent sides of the blocks had to match. This Japanese lantern effect required careful planning as they built their blocks and sewed them together. The combination of these two techniques is unusual. Since these two quilters probably lived within 10 miles of each other, were they working in a local or regional style? This method of creating a Courthouse Steps effect is not common in other states.

Elizabeth, the maker of this Amish quilt, used wool scraps while Clara, the “English” quilter, used silk scraps. It would be unusual for an Amish quilter to use silk pieces; however, “English” Log Cabin quilts often also use wool scraps, especially those made in the 1870s and ’80s. Both quilters used a large number of different fabrics to make their quilts. This variety may indicate that they shared and traded fabrics with other quiltmakers. Were they also sharing quiltmaking ideas? Elizabeth, the Amish quilter, used blocks of a larger size and therefore created a more simplified effect than Clara. Simplification of “English” designs seems to be part of the Amish aesthetic.

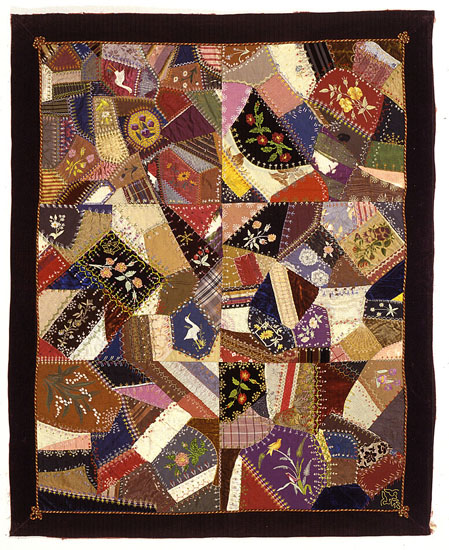

Crazy Quilt

Lydia J. Miller Beachy

c1900

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.64

Crazy Quilt

Mary Clara Rush Moore

c1880-1890

Arcola, Douglas County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1975.10 (746956)

The crazy quilt developed at about the same time as the Log Cabin quilt. Both quilts were usually made using a foundation fabric to which patches were sewn. Both styles were popularized through ladies’ magazines and newspapers. “English” quilters used up scraps of silk and velvet fabrics left over from the sewing of their dresses. They could also trade fabrics with friends or purchase scraps by mail. Amish quilters used nothing fancier than cotton sateen in their clothing, so it is not surprising that this Amish interpretation of the crazy quilt is made with cotton sateen—a fabric that had a similar shine to silk but was less expensive and more practical.

“English” quilters enjoyed embellishing their crazy quilts with elaborate embroidery stitches. As Clara did, the “English” embroidered flowers, birds, and other figures in the center of plain patches and decorated every seam with a wide variety of stitches. Clara’s quilt was made at about the time of her marriage in 1887 and may have served to showcase her skill as a needlewoman and, therefore, her preparation for married life. Lydia’s Amish quilt has only a few embroidery stitches—perhaps an experiment that was abandoned because it was too fancy or too time-consuming. However, the piecing of Lydia’s quilt is more complex. Lydia made 108 small blocks for her quilt, while Clara made only 6 large blocks. In keeping with the Amish aesthetic, Lydia has simplified the crazy quilt but also created a dynamic visual effect with a limited palette of colors.

It is interesting to speculate whether these two women might have met. They are very close in age and lived within 10 miles of each other. They were probably shopping at the same stores in Arthur and Arcola—although they had little opportunity to socialize. Perhaps Amish quilters were exposed to “English” quilts at county fairs where crazy quilts were judged in their own special categories and were highly prized. Evidently Illinois Amish quilters enjoyed the freedom of crazy piecing; however, fancy embroidery didn’t seem to catch hold in the Amish community, as none of its surviving crazy quilts have more than Lydia’s few stitches.

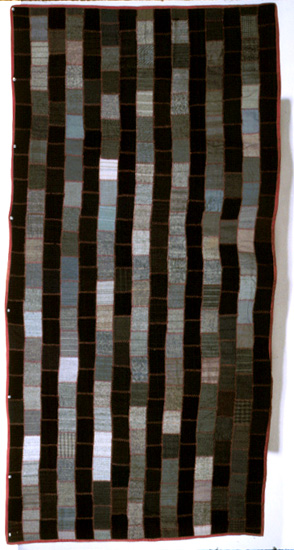

Brickwork

Agnes Stansfield

c1878

Mt. Carmel, Wabash County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1977.22 (747510)

Brick Wall

Magdalena Fisher Yoder

c1910

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.18

One patch quilts, using patches of the same size and shape, were popular among “English” and Amish quilters. Rectangular patches were called Bricks and could be pieced together in the same pattern used by a mason to build a wall. Sometimes these quilts were made from sample suiting fabrics that were used in dry-goods stores. Agnes Harmon Stansfield collected these samples from the Honest Corner Department Store where she worked in Mt. Carmel, Illinois. The store was founded in 1874 and Agnes married the owner, George Stansfield, in 1882. Agnes chose to sew feathered embroidery stitches along the seamlines of her Brick Wall piecing.

Magdalena Fisher Yoder also used many wool pieces that appear to be suiting samples. She sewed them together in the Brick Wall pattern—but without the decorative embroidery. Both quilters used cotton sateen for the backing of their quilts; however, Agnes chose to tie the layers together, while Magdalena used wool batting and quilted the layers together with her distinctive style of quilting alternating rows of patterns. Two of Magdalena’s other quilts using this style of quilting are also part of this exhibit. Agnes chose to emphasize the vertical rows by placing darker patches in alternating vertical rows. Magdalena offset her darker patches in adjacent rows, creating a diagonal effect. As is typical with “English” one patch quilts, Agnes didn’t use borders on her quilt. However, Magdalena chose a border treatment that is often seen on Illinois Amish quilts—border widths on the sides that are different from those on the top and bottom.

Agnes lived in Mt. Carmel, Illinois, an early settlement along the Wabash River in southeastern Illinois. Magdalena lived about 130 miles north in the Arthur Amish community. Their Brick Wall quilts are examples of a national trend, popularized through publications, such as the Ladies’ Art Company catalog. The use of suiting samples for quiltmaking is mentioned in The Dictionary of Needlework (1882) by Caulfeild and Saward. The making of these Brick Wall quilts may be more common than the number of surviving examples indicate, because many may have been destroyed through use.

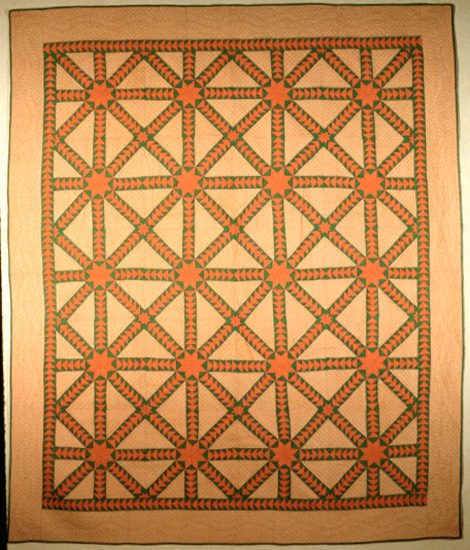

Rocky Road to California

Magdalena Fisher Yoder

c1910

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#2001.56

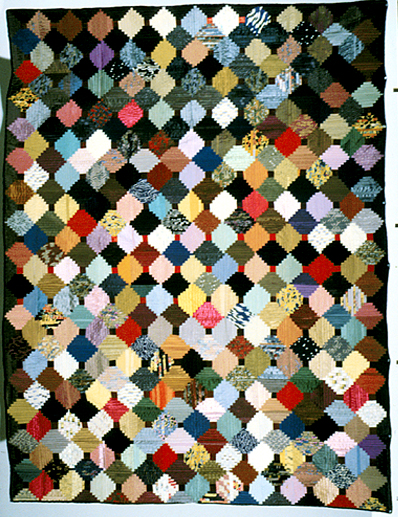

Tangled Cobwebs

Florence Irene Garvey

c1930-1950

Springfield, Sangamon County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1993.31.2

By the early 1900s, Amish and “English” quilters were attracted to more complicated pieced block patterns. They saw these patterns published in newspapers, magazines, and mail-order quilt-pattern catalogs. Quilters stored these patterns in boxes that they often stashed under their beds. Quilt historians today are eager to document this ephemera for insight into design sources and dates of popularity of patterns. “Boxes Under the Bed,” initiated by the Quilt Alliance, is one of these projects that has alerted families of quilters to the importance of these collections. Pattern boxes from three Amish quilters from Arthur were collected with the Illinois Amish Quilt Collection. These samples indicate that Illinois Amish quilters were not designing in isolation but were connected to the larger quilt world outside their community.

Amish quilter Magdalena Fisher Yoder chose a pattern that was published in the Ladies’ Art Company (LAC) catalog in the 1890s. This mail-order business, operating from St. Louis, pulled together many quilt-block pattern ideas from newspapers, magazines, and other sources, and offered quilters the opportunity to buy templates to make the block from a catalog of over 400 patterns. The catalog identified each pattern with a one-inch square drawing, a number, and a name. Magdelana’s quilt block was called Rocky Road to California, and that is also the name given the pattern by the quilter’s surviving family. Because of the widespread distribution of their catalog for over 60 years, the LAC was influential in standardizing quilt-pattern names. The early LAC patterns did not offer instructions on how to sew the blocks together, and Magdalena chose to turn the blocks to form the crossing diagonals in this quilt.

The strong diagonals in the orange-and-green quilt are pieced with small triangles that form a complex grid with stars at junctions. Variations of this pattern, called Tangled Cobwebs and Spider Web, were published in the 1930s Home Arts Studios catalog and a Mrs. Danners pamphlet of quilt patterns. This quilt from the estate of Florence Irene Garvey in Springfield was probably made by her or a family member. The use of only solid-color fabrics in this quilt is unusual for the 1930s when small pastel prints were the vogue. Amish quilters often used solid-color fabrics in the 1930s, and this quilt might mistakenly be identified as Amish were its history not known.

Cluster of Stars

Gertrude Schrock Stutzman

1923

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.83

Cluster of Stars

Hattie R. Conley Atkinson

c1915

Fairfield, Wayne County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1987.45.6

These two quilts offer the unusual opportunity to compare Amish and “English” quilts made from the same commercial pattern. The Cluster of Stars pattern was published in the Ladies’ Art Company catalog but may also have been published in a newspaper, magazine, or other source. The basic block consists of five Evening Star blocks placed in a Nine Patch grid. The same Evening Star block is placed as the cornerstones of the sashing. The simplification of the design by Amish quilter Gertrude Schrock Stutzman is achieved by her use of a larger scale, only two colors of solid fabric, and a single border. Hattie Conley Atkinson created more blocks, used many different fabrics in her stars, and used a triple border. Gertrude also chose to use her pink background color in the center of her stars, while Hattie chose to use the same fabric for the center and points of most of her stars.

While Gertrude simplified the piecing of her quilt, she chose to do a number of complicated feather quilting patterns—circles, bands, and vines. Hattie quilted an allover grid. Gertrude also created a more complicated back—piecing an inner border that allows the back to be used as an Amish Center Square quilt. Gertrude made her quilt as a gift to her daughter and dated it 1923 in the quilting. It was made to be a special quilt and has been carefully preserved in the family. Even though Hattie created her quilt for everyday use, she spent many hours piecing it and created a colorful red, white, and blue design at her farm home about 114 miles south of Gertrude’s home.

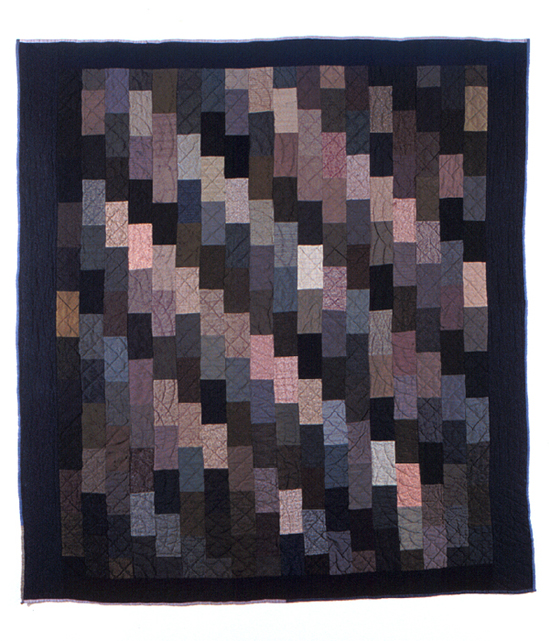

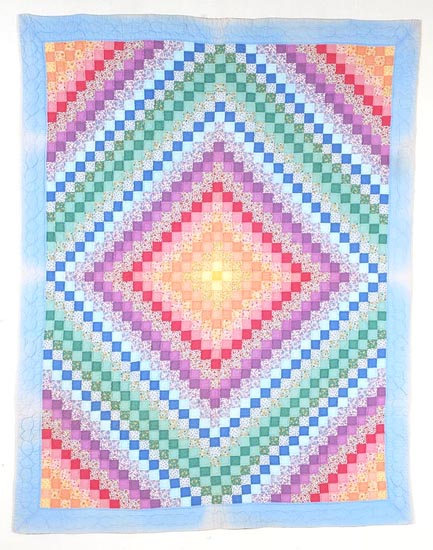

Sunshine and Shadow Bricks

Amanda Mast Schrock

c1935

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.43

Rainbow Quilt

Dorothy Wright Jones

c1933

Springfield, Sangamon County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#2004.25.180

One Patch quilts using a square patch placed in color bands radiating out from the center were popular with both Amish and “English” quilters in the 1930s. As with this “English” example, most of these quilts were made with square patches; however, Amanda Mast Schrock used rectangles, called Bricks, for her Amish quilt. The radiating design is often called Trip Around the World or Postage Stamp among “English” quilters. Sunshine and Shadow is the pattern name given to Amish quilts. The Amish quilt is made from only solid-color fabrics, as is typical, while the “English” quilt is made from both solid and printed fabrics.

While Amanda pulled fabrics from her scrap bag, Dorothy purchased a quilt kit at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933 to make her quilt. Her kit included instructions for piecing and all the fabrics, including the precut 1¾-inch squares necessary to make the top. Although Dorothy was an excellent seamstress, this is the only quilt that her daughter remembers her making. Dorothy was inspired to make the quilt after viewing the Century of Progress quilts made for the Sears Contest at the Fair. The kit she purchased was called Rainbow quilt. Amanda and Dorothy both used sewing machines to piece their quilts and then stitched them by hand with outline quilting inside their patches—a common practice in the 1930s.

Amanda and Dorothy were the same age and lived about 70 miles apart in the 1930s. Amanda’s rural life was probably very different from Dorothy’s urban life. It is likely that Dorothy had electricity and central plumbing in her home and Amanda didn’t. Amanda had seven daughters and one son to help with the household and farm chores, Dorothy’s husband was a realtor and she had only one daughter. However, their similar quilts illustrate a common quiltmaking experience.

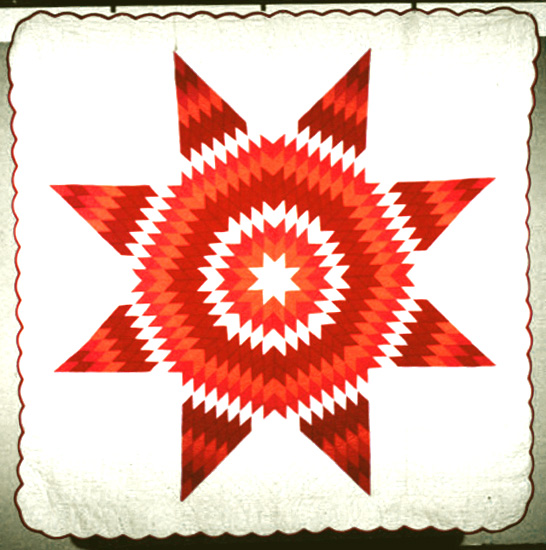

Star of Bethlehem

Emily Hetherington Hewett

1932

Amboy, Lee County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1978.22 (747552

Lone Star

Sovilla Schrock Kauffman

c1950

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.85

Lone Star designs have been made since the 1830s, but they seem to have gained popularity in the 1940s in Illinois, where they were made by both Amish and “English” quilters. The Lone Star (or Star of Bethlehem) pattern is constructed from diamond-shaped patches that are pieced into a large center medallion star. The placement of color in rings makes the Lone Star burst with visual energy. Quilt-pattern pamphlets, such as Aunt Martha’s Quilt Designs: Old Favorites and New, published directions and provided templates for making Lone Star quilts. The Illinois State Museum collection includes 12 quilts based on the Lone Star style, most made between 1930 and 1960.

These two Illinois Lone Star quilts illustrate a typically complex “English” version and a simplified Amish version. In Amboy, Illinois, about 187 miles northwest of the Arthur Amish community, “English” quilter Emily Hetherington Hewett made a Lone Star quilt that is a typical rendition of the pattern. Her quilt is made from small diamonds that circle the center star in seven color rings and fill the points with seven additional rows. Amish quilter Sovilla Schrock Kauffman simplified this design by enlarging the diamond and using only three color rings. Sovilla filled the corners of the star with four smaller stars. Although her center star is simplified, Sovilla added complexity and interest to her quilt with a double border, color variations, and a variety of quilting patterns.

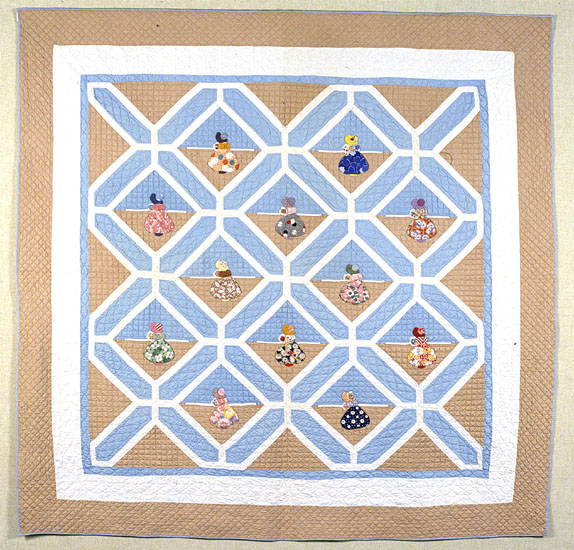

Tangled Garters

Bertha Stenge

c1940

Chicago, Cook County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1996.69

Variable Star in Garden Maze

Magdalena Bontrager Helmuth

c1940

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.10

The quilt blocks in these two quilts are sewn together with a complicated pieced sashing, used as early as the 1830s. “English” quilter Bertha Stenge placed her sashing on the diagonal to connect her Colonial Lady appliqué blocks. Amish quilter Magdalena Helmuth used a pieced block, Variable Star, and squared the sashing. Bertha and Magdalena may have discovered it in one of two popular quilt books. Ruth Finley’s Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them (1929) was an early attempt to write about quilts as historical artifacts. Finley recalled three names for this block—Garden Maze, Tangled Garter, and Tirzah’s Treasure—and pictured it with a plain block in the center. In 1935 Carrie Hall’s work to make a sample block of every published quilt pattern was illustrated in The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt in America. Hall used names from Finley’s book and added the name Sun Dial.

Bertha Stenge named her quilt Tangled Garters, a lesser-known name for this pattern today. Garters were bands used to hold up stockings, and Bertha may have chosen it because of the gowned females she appliquéd in the center squares. With the large hat hiding the face, and the full dress, her design is similar to the Sunbonnet Sue design that was so popular from the 1920s to ’50s. Like many quilters in the 1930s and early 1940s, Bertha chose pastel colors for her quilt and used scraps of floral print fabric. Bertha was an exceptional quilter and artist and won many national prizes for needlework of her own design. Bertha, like many of her urban neighbors, was attracted to quiltmaking as a result of the Colonial Revival movement in the decorative arts, promoted in many women’s magazines.

Magdalena Helmuth chose to use a pieced pattern inside her Garden Maze sashing. The Variable Star is a popular nine-patch-based pattern among the Illinois Amish. However, it is unusual for the Amish to use Garden Maze sashing and a relatively large amount of white fabric. Blue is a much more common choice for Illinois Amish clothing and quilts. This quilt illustrates the unexpected extent of influence of “English” published patterns and color trends on the Amish.

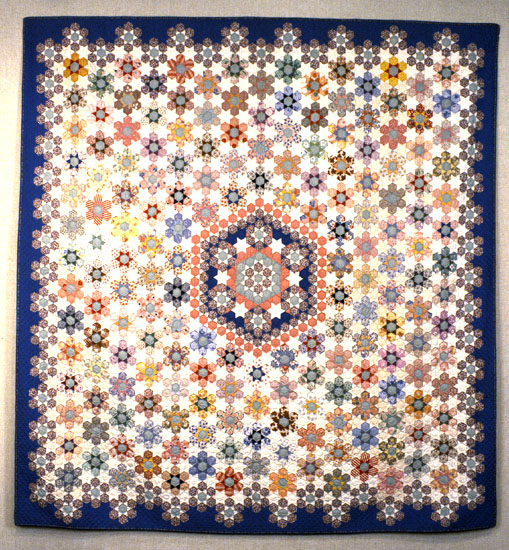

Framed Star

Emma D. Yoder Beachy

c1940

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.123

Star of Contstantine

Bertha Stenge

1936

Chicago, Cook County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1995.159.2

The traditions of center medallion and framed quilts were practiced by Illinois Amish quilters and, to a lesser extent, by Illinois “English” quilters. A center medallion quilt features a large center design with one or two borders, while a framed quilt has a smaller center design with many borders.

The Amish quilt here is one of seven framed quilts in the Illinois Amish Quilt Collection. From surviving examples, it appears that framed quilts were more popular in England than in America and were not common in other Amish communities. It is surprising that so many were found in the Arthur Amish community. Emma Beachy’s framed quilt was constructed of scraps of fabric, probably left over from sewing clothing for her family. The colors of blue, green, and purple were popular among the Illinois Amish. The breaking of expected patterns, such as the changes of coloring in the border, suggests that the quilt was assembled somewhat spontaneously—a visually interesting effect often seen in Illinois Amish quilts.

Although both quilts feature a star design in the center, Bertha Stenge’s “English” quilt is built with hexagons and triangles, while Emma Beachy’s eight-pointed star is built from diamonds. “English” quilters made many hexagon-based patterns from the early 1800s, when the pattern was called Mosaic, to the 1930s, when Grandmother’s Flower Garden quilts were popular. No quilts based on hexagons were found among the 160 quilts in the Illinois Amish Quilt Collection. Bertha was inspired to make this quilt by an antique plate she saw at the Art Institute of Chicago. She made this quilt from 7,200 pieces of fabric in 500 colors and entered it in the Canadian National Exposition contest in 1936, where she won her first national prize.

Basket

Fannie Beachy Mast

c1940

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.5

Tulip Cross

Janet or (her mother) Angie Weston

c1930s

Champaign, Champaign County, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1995.104.154

In both of these Amish and “English” quilts, block designs are set on point and alternated with plain blocks. This method of sewing blocks together is a very old tradition equally popular among Amish and “English” quilters. The plain squares provide a blank canvas for the stitching of elaborate quilting designs. The feathered wreath quilting design found on the Weston quilt was also typically used by Amish quilters.

The most striking differences in these two quilts are the choices in block patterns and colors. They each illustrate their respective Amish and “English” design preferences. Amish quilter Fanny Beachy Mast chose a pieced basket pattern. The Amish in Illinois preferred piecing to appliqué—perhaps because pieced patterns were less realistic and less fancy. Fanny may have seen this basket pattern in the Ladies’ Art Company catalog or in newspapers such as The American Farmer, Progressive Farmer, or Chicago Tribune. This pattern was very popular from the 1920s to 1940s. Fanny chose green fabrics for her baskets and a bright yellow (unusual for Amish quilts) for the basket background and inner border. The blue background was often used by Illinois Amish quilters; however, it is darker than most “English” color choices at this time. “English” quilters during the 1920s were fascinated with appliqué designs and looked for design inspiration from the red and green floral quilts of the mid nineteenth century. Commercial pattern designers, such as Nancy Page and Nancy Cabot, often simplified these floral patterns to appeal to readers of their newspaper columns. The Tulip Cross pattern appliquéd on the “English” quilt here was published in the Ladies’ Art Company catalog and in many of the same sources where the basket pattern appeared. As pattern catalogs and magazines began to be printed in color, suggested color schemes for these quilts shifted popular aesthetics toward pastel colors. Some of these quilts were designed in the medallion style with a large appliqué design in the center and appliquéd borders. The Weston quilt, found in the family estate, has a more traditional block style but is typical of “English” fashions in appliquéd quilts of the 1920s to 1940s—one of the few quilt fashions not adopted by the Amish.

Jan Wass

Illinois State Museum, 2011

All rights reserved

-

Museum

Illinois State Museum Illinois State Museum

-

Ephemera

Amish and "English": Quilts from the I...

Jan Wass

-

Exhibit

Amish and "English": Quilts from the I...

Wass, Jan

-

1850-1875

Scrap Quilt Yoder, Magdalena Fi...

-

1850-1875

Scrap Foster, Matilda Ann...

-

1876-1900

Nine Patch Gingerich, Catherin...

-

1876-1900

Nine Patch Foster, Matilda Ann...

-

1876-1900

Square on Point -

1876-1900

Hexagon and Diamo... Black, Sarah Vaughn...

-

1901-1929

Log Cabin Mast, Elizabeth Bri...

-

1901-1929

Log Cabin Courtho... Moore, (Mary) Clara...

-

1901-1929

Crazy quilt Beachy, Lydia J. Mi...

-

1876-1900

Crazy Moore, Mary Clara R...

-

1901-1929

Brick Wall Yoder, Madgalena Fi...

-

1876-1900

Brickwork (LAC 29... Stansfield, Agnes S...

-

1901-1929

Rocky Road to Cal... Yoder, Magdalena Fi...

-

1930-1949

Tangled Cobwebs Garvey, Florence Ir...

-

1923

Cluster of Stars ... Stutzman, Gertrude ...

-

1901-1929

Cluster of Stars Atkinson, Hattie R....

-

1930-1949

Sunshine and Shad... Schrock, Amanda Mas...

-

1930-1949

Rainbow Quilt Jones, Dorothy Wrig...

-

1950-1975

Lone Star Kauffman, Sovilla S...

-

1930-1949

Star of Bethlehem... Hewett, Emily Hethe...

-

1930-1949

Variable Star in ... Helmuth, Magdalena ...

-

1930-1949

Tangled Garters Stenge, Bertha

-

1930-1949

Framed Star Beachy, Emma D. Yod...

-

1930-1949

Star of Contstant... Stenge, Bertha

-

1930-1949

Basket Mast, Fannie Beachy...

-

1930-1949

Tulip Cross (LAC ... Weston, Janet ?; We...

Load More