BACK TO EXHIBITS

Amish and "English": Quilts from the Illinois State Museum

March 15 - September 16, 2011

Amish and "English": Quilts from the Illinois State Museum Collection

Illinois State Museum Lockport Gallery

This comparative exhibit of Amish and “English” quilts from the Illinois State Museum collection dispels the notion that Amish quilts were made in isolation from larger American trends. In Illinois, Amish and “English” quilters were using the same fabrics, techniques, colors, formats, and patterns, with only a few exceptions. The Amish didn’t use print fabrics in quilts made for their own use because of their religious beliefs, and they rarely used applique patterns or large amounts of white fabric.

American quilts are remarkable for their variety—achieved through fabrics, techniques, color palettes, formats, and patterns. Available fabrics and popular trends have influenced American quiltmaking, from the first colonial chintz quilts through the commercialization of quiltmaking in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Because the Amish have sought separation from the “English” world in many aspects of their life, it is tempting to assume that their quilts were also made in isolation from larger American trends. This comparative exhibit of Amish and “English” quilts from the Illinois State Museum collection dispels this notion. In Illinois, Amish and “English” quilters were using the same fabrics, techniques, colors, formats, and patterns, with only a few exceptions. The Amish didn’t use print fabrics in quilts made for their own use because of their religious beliefs, and they rarely used appliqué patterns or large amounts of white fabric.

Similarities in the quilts can be expected, since current evidence suggests that the Amish first learned quiltmaking in the 1830s from their “English” neighbors. They were using the same sources for fabrics—local stores, peddlers, and mail-order catalogs. The Amish also learned about quilt patterns through newspapers and magazines popular with farm families, and they saw “English” quilts at county fairs, where quiltmaking competitions exposed them to such new styles as log cabin and crazy quilts. “English” quilters also made quilts using only solid-color fabrics, and examples of this are in this exhibition. Such quilts could be mistaken as Amish, if their histories were not known.

Some differences are subtle. The Illinois Amish tended to prefer simpler pieced patterns and sometimes adapted “English” patterns by enlarging a block pattern or by using fewer but larger pieces. Amish colors were generally darker, even during the pastel trend in the 1920s and ’30s. Sometimes the Amish quilted more complicated patterns, especially feathering. This emphasis on quilting can be seen even in their early handwoven wool quilts. The Amish rarely used silk fabrics when silks were popular among the “English” for crazy quilts and log cabin piecing. The Amish continued to use wool fabrics in their quilts in the early 1900s when “English” quilts were mostly cotton. All of these similar and different characteristics illustrate that both Amish and “English” quilts are part of the diversity that defines American culture.

Who are the Amish?

The Amish are a conservative, pacifist Christian religious group with origins in the Protestant Reformation in sixteenth-century Germany and Switzerland. They were named for their founder, Jacob Ammon. The first Amish people came to Pennsylvania in 1737, seeking religious freedom. As Amish families followed the westward expansion of America, some settled in east central Illinois, near Arthur, in 1865. Religion is integral to all aspects of Amish life, and nonconformity to the secular world around them is symbolic of their devotion. The Amish reject many aspects of modern technology—gas-powered vehicles, telephones, and high-power electricity—that they feel could disrupt the cohesion of the community. Dress is modest and uniform, and only solid-color fabrics are used. Photography of individuals is considered idolatrous. Today the Amish community in Arthur consists of about 4,200 residents.

Who are the “English?”

Because the Amish speak a Germanic dialect among themselves, they refer to all people outside their community as “English.” The term is confusing because the Amish also speak English, and other people with Germanic ethnicity are still considered “English” to the Amish. Non-Amish is a less colorful but more accurate term for “English.” The “English” quilters represented in this exhibit are from many ethnic and religious backgrounds—German, English, Irish, Polish, Cherokee, Methodist, and Jewish—but they were all born in America and are foremost Americans—as are the Amish.

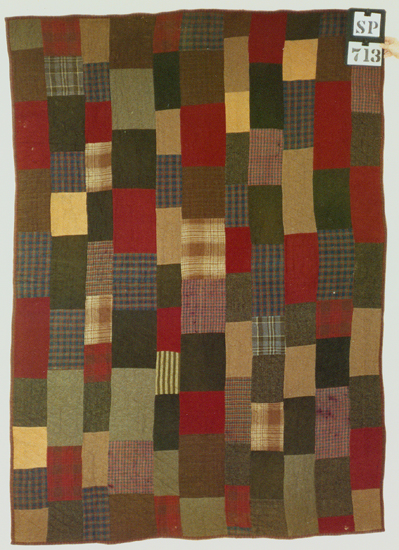

Amish: Scrap Quilt

Magdalena Fisher Yoder (1850-1937)

c1875

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.17

Wool, machine pieced, and hand quilted with alternating rows of diagonal parallel lines and fans in center, and fans in border. Tan cotton backing, cotton batting and applied brown cotton twill binding.

Enlish: Scrap Quilt

Matilda Ann Jones Foster (1852-1931)

c1870

Mt. Zion, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1974.17 (746932)

Wool, hand pieced, and quilted with allover pattern of diagonal parallel lines. Brown wool backing, wool batting, and brown wool binding.

To warm the beds of rural homes, Illinois women often made quilts from scraps of wool left over from making clothing. As with both of these examples, quilters sometimes used handwoven fabrics, as well as early mill-woven fabrics. Spinning and weaving equipment was common in Illinois farm homes as late as the 1870s. Small local woolen mills also served regional needs. The disruption of the cotton trade during the Civil War probably was a large factor in the use of wool fabrics in Illinois at this time. Matilda used many plaid fabrics that were very popular among the “English.” Magdalena’s choice of solid-color fabrics reflects her plainer Amish tastes; however, she added an interesting visual texture to her quilt by using a few pieces of a handwoven alternating-thread-color fabric (red and blue).

These utility quilts were often simply pieced with no particular pattern in mind. Matilda Ann sewed rectangles of similar widths together to make long strips that she then sewed together—no need to match seams. Magdalena chose to work with a 6 ½-inch-square format and to cut her scraps to fit—sometimes piecing smaller squares or rectangles together to make the square and carefully matching the seams when sewing the rows together to form a checkerboard. Although only a few of these utility quilts have survived, the eight in the Illinois State Museum’s collection suggest that it was more common for “English” quilters to use wool batting and for Amish quilters to use cotton. “English” wool utility quilts were commonly stitched with allover patterns of diagonal lines or fans, while the Amish seemed to use a variety of quilting patterns. In the four quilts in the Museum’s collection, Magdalena used alternating bands of designs—a style that seems to be her own.

Matilda Ann and Magdalena were very close in age and lived about 30 miles from each other in central Illinois. Their lifestyles before electricity came to rural Illinois would have been similar; however, Magdalena pieced with a treadle sewing machine, while Matilda Ann pieced by hand. Sewing machines were becoming affordable and available in Illinois during the 1870s, and Magdalena’s quilt was probably made later than Matilda Ann’s. However, “English” quilters in Illinois evidently preferred hand piecing even into the twentieth century.

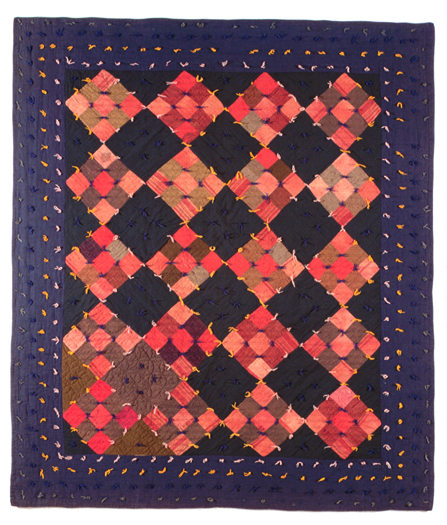

Amish: Nine Patch Comforter

Possibly made by Catherine Miller Gingerich (1861-1931)

c1880

or Iowa or an Illinois relative

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.59

Wool, hand and machine pieced, hand quilted with double parallel lines in pieced blocks and overlapping circles in plain blocks, and tied with wool yarn in four colors. Dark blue cotton backing, unknown batting fiber, and binding is back turned to front and hand sewn.

English: Nine Patch Comforter

Matilda Ann Jones Foster

c1880

Mt. Zion, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1974-17 (746936)

Wool, hand pieced, and tied with brown wool yarn. Brown wool backing pieced with scraps, some handwoven and some machine knitted, cotton batting, and edges turned in as binding, and buttonhole stitched.

The Nine Patch block is one of the most common and basic pieced blocks used by Amish and “English” quilters alike. Squares, each divided into nine smaller squares, could be sewn together with sashing strips or with alternating unpieced squares, creating an overall pattern that is more geometrically controlled than that of a scrap quilt. Amish and “English” quilters in Illinois worked in both of these sets, or styles, of sewing blocks together.

Both of these wool comforters contain patches of handwoven fabrics and have thick batting. Although the thickness of the batting and fabrics would have made hand quilting difficult, the Amish bed cover was hand quilted, with different patterns in the plain and pieced blocks. The “English” comforter was tied with knots in a regular pattern to keep the layers together. The Amish comforter was also tied with rows of knots of different colored thread in the border, as well as in the center. Layered bed coverings that are tied and not quilted are usually called comforters, or comforts. This Amish bed cover is difficult to categorize. Is it a quilt or a comforter? It may have started out as a quilt, sustained some damage, and was then transformed into a comforter. Dark gray patches have been appliquéd over worn areas of lavender on the top. This repair appears old, as do the tied knots.

The Amish comforter descended in the family of Catherine Miller Gingrich, who they believed made it. No evidence has been found that Catherine ever lived in Illinois; however her aunt, Barbara Miller Yoder, was one of the first women to settle in Illinois in 1865. The distinctive red and blue alternating-thread-color fabric found in this comforter is also found in many of the early Illinois quilts associated with this family. Could Catherine have been inspired to make this comforter after visiting Illinois from her home in Iowa, or could it have been a gift from an Illinois relative? Though many questions remain, the similarities with other Illinois quilts are notable. Matilda, the “English” quilter, also made a scrap quilt in this exhibit. She lived about 30 miles from the Arthur Amish community.

Amish: Log Cabin Courthouse Steps

Probably made by Elizabeth Briskey Mast (1876-1950)

c1900

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.12

Wool, cotton, and plush, machine pieced on white muslin foundation, and hand quilted with diagonal parallel lines on back only. Blue cotton backing, cotton batting, and appliqued black cotton binding.

English: Log Cabin Courthouse Steps

(Mary) Clara Rush Moore (1867-1949)

c1910

Arcola, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1975.10 (746955)

Silk and other scrap fabrics, hand pieced, and tied with pink perle cotton yarn. Green rayon backing, no filling, and black rayon binding.

Log Cabin quilts were popular among “English” quilters from the 1870s through the 1910s. The basic block is made by starting with a small square and sewing narrow strips of fabric in sequence around all four sides, enlarging the block as it is “built.” The most commonly used construction method involved adding the strips around adjacent sides of the square with light and dark color strips placed to visually divide the block into half diagonally. A less common method, called Courthouse Steps, involved sewing the strips in sequence on opposite sides of the square. Light colors are placed on opposite sides and dark colors on the other sides, dividing the square into quarters diagonally. Sometimes each quarter is filled with the same fabric or similar fabrics.

These two Illinois quilters used ideas from both Log Cabin techniques to create their similar quilts. They used the basic Log Cabin construction (adding strips to adjacent sides) and Courthouse Steps coloration (with the same fabric in each quarter). To create the effect of squares of color on point, colors on adjacent sides of the blocks had to match. This Japanese lantern effect required careful planning as they built their blocks and sewed them together. The combination of these two techniques is unusual. Since these two quilters probably lived within 10 miles of each other, were they working in a local or regional style? This method of creating a Courthouse Steps effect is not common in other states.

Elizabeth, the maker of this Amish quilt, used wool scraps while Clara, the “English” quilter, used silk scraps. It would be unusual for an Amish quilter to use silk pieces; however, “English” Log Cabin quilts often also use wool scraps, especially those made in the 1870s and ’80s. Both quilters used a large number of different fabrics to make their quilts. This variety may indicate that they shared and traded fabrics with other quiltmakers. Were they also sharing quiltmaking ideas? Elizabeth, the Amish quilter, used blocks of a larger size and therefore created a more simplified effect than Clara. Simplification of “English” designs seems to be part of the Amish aesthetic.

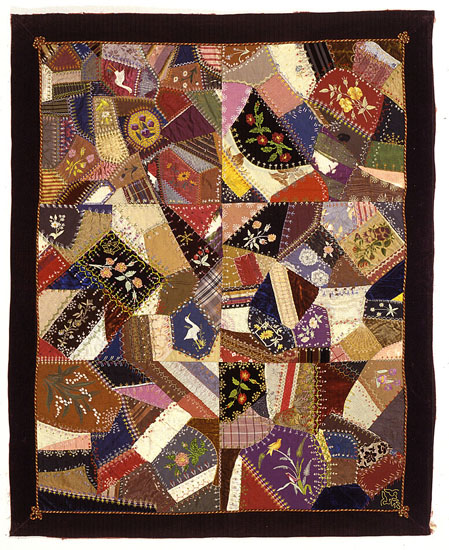

Amish: Crazy Quilt

Lydia J. Miller Beachy (1863-1925)

c1900

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.64

Cotton sateen, hand foundation pieced and quilted with diagonal parallel lines. Red cotton backing, no batting, and applied black cotton-sateen binding.

English: Crazy Quilt

(Mary) Clara Rush Moore

c1880-1890

Arcola, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1975.10 (746956)

Silk, hand foundation pieced, tied with pink thread. Red silk backing, cotton batting, edges turned in for binding.

The crazy quilt was a quilt trend that developed about the same time as the Log Cabin quilt. Both quilts were usually made using a foundation fabric to which patches were sewn. Both styles were popularized through ladies’ magazines and newspapers. “English” quilters used up scraps of silk and velvet fabrics left over from the sewing of their dresses. They could also trade fabrics with friends or purchase scraps by mail. Amish quilters used nothing fancier than cotton sateen in their clothing, so it is not surprising that this Amish interpretation of the crazy quilt is made with cotton sateen—a fabric that had a similar shine to silk but was less expensive and more practical.

“English” quilters enjoyed embellishing their crazy quilts with elaborate embroidery stitches. As Clara did, the “English” embroidered flowers, birds, and other figures in the center of plain patches and decorated every seam with a wide variety of stitches. Clara’s quilt was made at about the time of her marriage in 1887 and may have served to showcase her skill as a needlewoman and, therefore, her preparation for married life. Lydia’s Amish quilt has only a few embroidery stitches—perhaps an experiment that was abandoned because it was too fancy or too time-consuming. However, the piecing of Lydia’s quilt is more complex. Lydia made 108 small blocks for her quilt, while Clara made only 6 large blocks. In keeping with the Amish aesthetic, Lydia has simplified the crazy quilt but also created a dynamic visual effect with a limited palette of colors.

It is interesting to speculate whether these two women might have met. They are very close in age and lived within 10 miles of each other. They were probably shopping at the same stores in Arthur and Arcola—although they had little opportunity to socialize. Perhaps Amish quilters were exposed to “English” quilts at county fairs where crazy quilts were judged in their own special categories and were highly prized. Evidently Illinois Amish quilters enjoyed the freedom of crazy piecing; however, fancy embroidery didn’t seem to catch hold in the Amish community, as none of its surviving crazy quilts have more than Lydia’s few stitches.

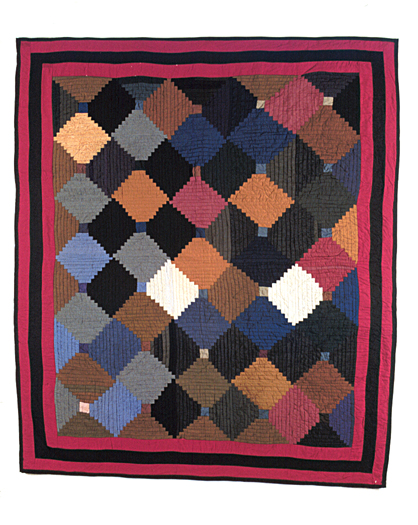

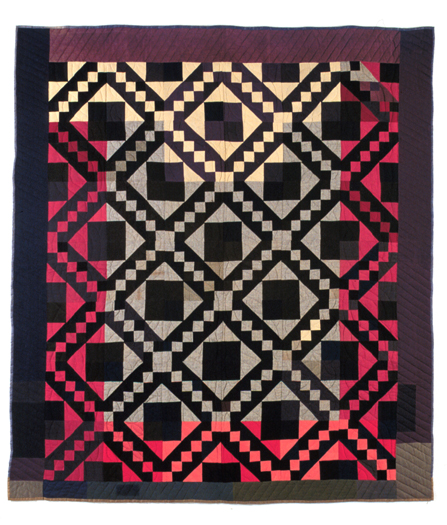

Amish: Rocky Road to California

Magdalena Fisher Yoder (1850-1937)

c1910

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#2001.56

Wool, machine pieced, and hand quilted with alternating vertical rows of four-line classic cables and overlapping circles, and diagonal parallel lines in border. Dark blue-purple cotton sateen backing, thick wool batting, and backing folded to front as binding.

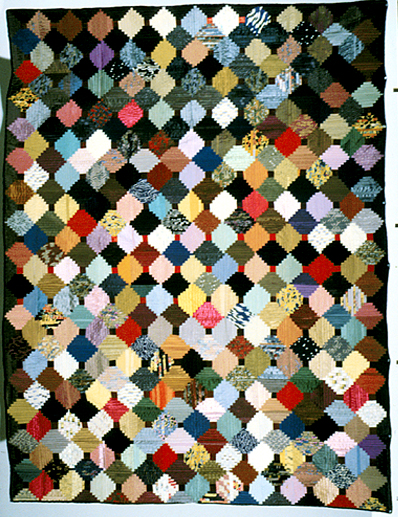

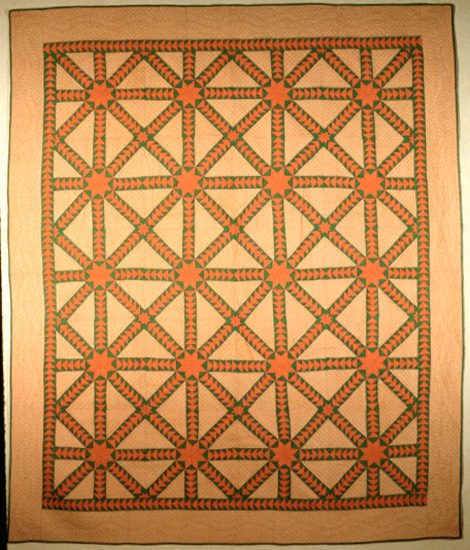

English: Tangled Cobwebs Quilt

Possibly Florence Irene Garvey (1903-1993)

c1930-1950

Springfield, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1993.31.2

Cotton, hand pieced, and hand quilted with outline quilting in triangles and feathered vine in border. Apricot cotton backing, cotton batting, applied binding.

By the early 1900s, Amish and “English” quilters were attracted to more complicated pieced block patterns. They saw these patterns published in newspapers, magazines, and mail-order quilt-pattern catalogs. Quilters stored these patterns in boxes that they often stashed under their beds. Quilt historians today are eager to document this ephemera for insight into design sources and dates of popularity of patterns. “Boxes Under the Bed,” initiated by the Quilt Alliance, is one of these projects that has alerted families of quilters to the importance of these collections. Pattern boxes from three Amish quilters from Arthur were collected with the Illinois Amish Quilt Collection. These samples indicate that Illinois Amish quilters were not designing in isolation but were connected to the larger quilt world outside their community.

Amish quilter Magdalena Fisher Yoder chose a pattern that was published in the Ladies’ Art Company (LAC) catalog in the 1890s. This mail-order business, operating from St. Louis, pulled together many quilt-block pattern ideas from newspapers, magazines, and other sources, and offered quilters the opportunity to buy templates to make the block from a catalog of over 400 patterns. The catalog identified each pattern with a one-inch square drawing, a number, and a name. Magdelana’s quilt block was called Rocky Road to California, and that is also the name given the pattern by the quilter’s surviving family. Because of the widespread distribution of their catalog for over 60 years, the LAC was influential in standardizing quilt-pattern names. The early LAC patterns did not offer instructions on how to sew the blocks together, and Magdalena chose to turn the blocks to form the crossing diagonals in this quilt.

The strong diagonals in the orange-and-green quilt are pieced with small triangles that form a complex grid with stars at junctions. Variations of this pattern, called Tangled Cobwebs and Spider Web, were published in the 1930s Home Arts Studios catalog and a Mrs. Danners pamphlet of quilt patterns. This quilt from the estate of Florence Irene Garvey in Springfield was probably made by her or a family member. The use of only solid-color fabrics in this quilt is unusual for the 1930s when small pastel prints were the vogue. Amish quilters often used solid-color fabrics in the 1930s, and this quilt might mistakenly be identified as Amish were its history not known.

Amish: Sunshine and Shadow Bricks

Amanda Mast Schrock (1889-1973)

c1935

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.43

Cotton, machine pieced, and hand quilted with outline quilting in rectangles. Piece backing made from cream, red, gray and tan cotton fabrics, another quilt used as filler, and applied maroon binding.

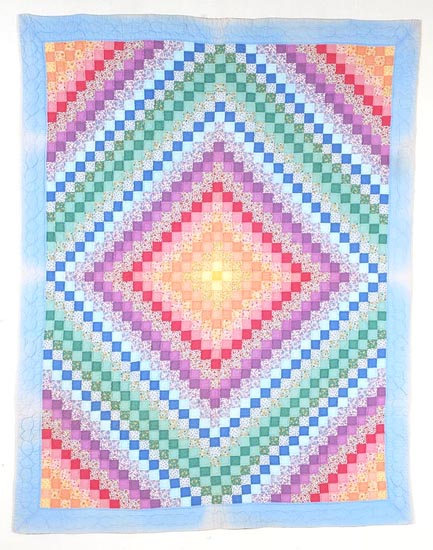

English: Rainbow Quilt

Dorothy Wright Jones (1889-1971)

c1933

Springfield, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#2004.25.180

Cotton, machine pieced, and hand quilted with outline quilting in squares and oval and diamond cable in border. Blue cotton backing, cotton batting, applied cotton binding.

One Patch quilts using a square patch placed in color bands radiating out from the center were popular with both Amish and “English” quilters in the 1930s. As with this “English” example, most of these quilts were made with square patches; however, Amanda Mast Schrock used rectangles, called Bricks, for her Amish quilt. The radiating design is often called Trip Around the World or Postage Stamp among “English” quilters. Sunshine and Shadow is the pattern name given to Amish quilts. The Amish quilt is made from only solid-color fabrics, as is typical, while the “English” quilt is made from both solid and printed fabrics.

While Amanda pulled fabrics from her scrap bag, Dorothy purchased a quilt kit at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933 to make her quilt. Her kit included instructions for piecing and all the fabrics, including the precut 1¾-inch squares necessary to make the top. Although Dorothy was an excellent seamstress, this is the only quilt that her daughter remembers her making. Dorothy was inspired to make the quilt after viewing the Century of Progress quilts made for the Sears Contest at the Fair. The kit she purchased was called Rainbow quilt. Amanda and Dorothy both used sewing machines to piece their quilts and then stitched them by hand with outline quilting inside their patches—a common practice in the 1930s.

Amanda and Dorothy were the same age and lived about 70 miles apart in the 1930s. Amanda’s rural life was probably very different from Dorothy’s urban life. It is likely that Dorothy had electricity and central plumbing in her home and Amanda didn’t. Amanda had seven daughters and one son to help with the household and farm chores, Dorothy’s husband was a realtor and she had only one daughter. However, their similar quilts illustrate a common quiltmaking experience.

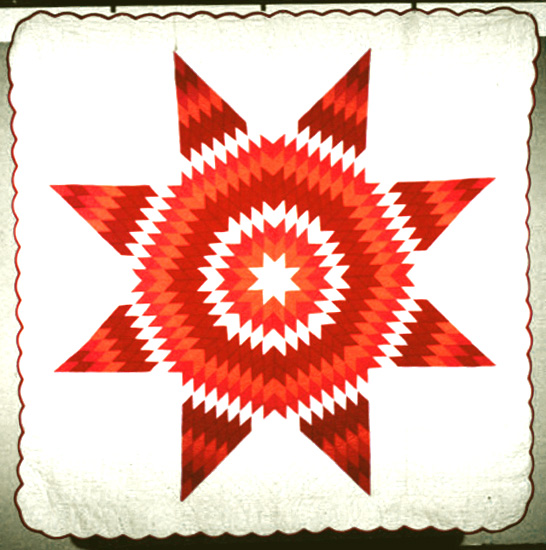

Amish: Lone Star Quilt

Sovilla Schrock Kauffman (1912-?)

c1950

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.85

Cotton, machine pieced and hand quilted with outline quilting in diamonds, grid in corner squares, clamshells in large triangles, two-line intersecting cable in inner border, and five-line classic cable in outer border. Cream rayon backing, white cotton blanket as filler, and applied backing fabric as binding.

English: Lone Star Quilt

Emily Hetherington Hewett

1932

Amboy, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1978.22 (747552

Cotton, hand and machine pieced, hand quilted with outline quilting in diamonds and square grid in background. White cotton back, cotton batting, and red bias binding.

The Lone Star (or Star of Bethlehem) pattern is constructed from diamond-shaped patches that are pieced into a large center medallion star. The placement of color in rings makes the Lone Star burst with visual energy. Lone Star designs have been made since the 1830s, but they seem to have gained popularity in the 1940s in Illinois, where they were made by both Amish and “English” quilters. Quilt-pattern pamphlets, such as Aunt Martha’s Quilt Designs: Old Favorites and New, published directions and provided templates for making Lone Star quilts. The Illinois State Museum collection includes 12 quilts based on the Lone Star style, most made between 1930 and 1960.

In Amboy, Illinois, about 187 miles northwest of the Arthur Amish community, “English” quilter Emily Hetherington Hewett made a Lone Star quilt that is a typical rendition of the pattern. Her quilt is made from small diamonds that circle the center star in seven color rings and fill the points with seven additional rows. Amish quilter Sovilla Schrock Kauffman simplified this design by enlarging the diamond and using only three color rings. Sovilla filled the corners of the star with four smaller stars. Although her center star is simplified, Sovilla added complexity and interest to her quilt with a double border, color variations, and a variety of quilting patterns.

Amish: Framed Star Quilt

Emma D. Yoder Beachy (1883-1959)

c1940

Arthur, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1998.152.123

Cotton, machine pieced, and hand quilted with outline quilting in star and chevrons in borders. Older dark blue cotton quilt serves as both backing and filler, applied light blue cotton binding.

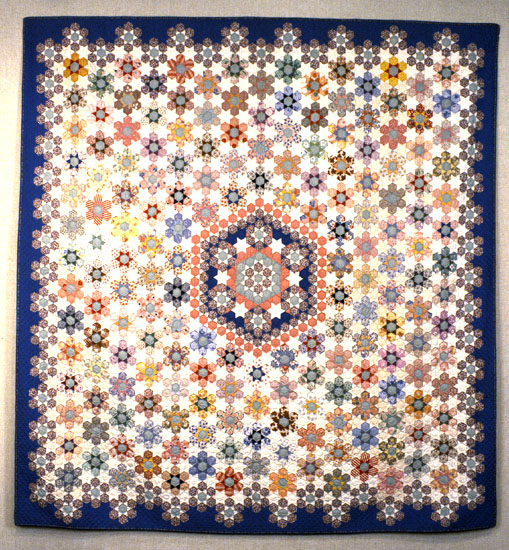

English: Star of Contstantine Quilt

Bertha Sheramsky Stenge (1851-1957)

1936

Chicago, Illinois

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1995.159.2

Cotton, hand pieced, and hand quilted with outline quilting in hexagons and diagonal grid border. Blue cotton backing, cotton batting, and applied cotton binding.

The traditions of center medallion and framed quilts were practiced by Illinois Amish quilters and, to a lesser extent, by Illinois “English” quilters. A center medallion quilt features a large center design with one or two borders, while a framed quilt has a smaller center design with many borders. This Amish quilt is one of seven framed quilts in the Illinois Amish Quilt Collection. From surviving examples, it appears that framed quilts were more popular in England than in America and were not common in other Amish communities. It is surprising that so many were found in the Arthur Amish community. Emma Beachy’s framed quilt was constructed of scraps of fabric, probably left over from sewing clothing for her family. The colors of blue, green, and purple were popular among the Illinois Amish. The breaking of expected patterns, such as the changes of coloring in the border, suggests that the quilt was assembled somewhat spontaneously—a visually interesting effect often seen in Illinois Amish quilts.

Although both quilts feature a star design in the center, Bertha Stenge’s “English” quilt is built with hexagons and triangles, while Emma Beachy’s eight-pointed star is built from diamonds. “English” quilters made many hexagon-based patterns from the early 1800s, when the pattern was called Mosaic, to the 1930s, when Grandmother’s Flower Garden quilts were popular. No quilts based on hexagons were found among the 160 quilts in the Illinois Amish Quilt Collection. Bertha was inspired to make this quilt by an antique plate she saw at the Art Institute of Chicago. She made this quilt from 7,200 pieces of fabric in 500 colors and entered it in the Canadian National Exposition contest in 1936, where she won her first national prize.

Quilts at the Illinois State Museum

Collectiong quilts has been a major interest at the Illinois State Museum since the 1950s, and, in keeping with the Museum's mission, quilts made in or connected to Illinois are emphasized. The Museum's over 300 quilts, part of the Decorative Arts Collection, reflect not only the trends in quiltmaking over 175 years but the artistry and craftsmanship of Illinois quiltmakers. Through the generous donations of family memers, nineteenth-century women are memorialized by their wholecloth, pieced, applique, crazy, and log cabin quilts in the museum's collection. Recently the museum has been actively collecting twentieth-century and contemporary quilts -- including the nationally known work of Bertha Stenge, Albert Small, Caryl Bryer Fallert, and M. Joan Lintault. Over 150 Illinois Amish quilts have recently been added to the collection.

The Quilt Exhibition Program at the Illinois State Museum is very active. Current and upcoming exhibitions are listed on the Museum's Web site: www.museum.state.il.us. The Illinois Amish Quilt exhibition has traveled to four of the museum's art galleries from 2000 to 2003 and will now be available for bookings nationally. Past quilt exhibits have included: Connecting Stitches (celebrating the Illinois Quilt Research Project); Patchwork Souvenirs of the 1933 World's Fair (curated by Merikay Waldvogel); A Cut and Stitch Above: The Quilts of Bertha Stenge (curated by Merikay Waldvogel and Janice Tauer Wass); Spectrum: The Textile Art of Caryl Bryer Fallert: Illinois Crossroads; Evidence of Paradise: The Quilts of M. Joan Lintault; Illinois Amish Quilts: Sharing Thread of Tradition; and Gifted Quilts.

An On-line Database of all the quilts in the Illinois State Museum is offered through the Quilt Index, a national database available at www.quiltindex.org. For the Quilt Index, quilts in the Museum's collection were analyzed for techniques, described by style, measured, and photographed. In many case microscopic analysis was used to determine batting and fabric fibers. The background information offered by families of donors was checked against historical records. The historical information and technical descriptions were compared with current quilt history scholarship to more accurately date these quilts and confirm the identity of their makers. The collected data and digital images were then added to the on-line database. As new quilts are added to the Illinois State Museum collection and new information becomes available, the Quilt Index will continue to be updated.

Preservation of Illinois quilt heritage is central to the mission of the Museum. Light levels are carefully monitored while quilts are on display. When not on display, quilts are stored in a state-of-the-art, climate-controlled vault in acid-free containers.

Generous Donations by individual and families make it possible for the Museum to present to you an understanding of the rich cultural heritage found in Illinois quilts. Please consider the Illinois State Museum as a home for your quilts. Generations to come will greatly benefit from your generosity.

Illinois State Museum Lockport Gallery

201 West 10th Street

Lockport, Illinois 30441

815.838.7400

http://www.museum.state.il.us/ismsites/lockport

Hours: Sunday, 12-5; Monday through Friday, 9-5

Closed Saturdays and State holidays

-

Museum

Illinois State Museum Illinois State Museum

-

Ephemera

Amish and "English": Quilts from the I...

Jan Wass

-

Essay

Amish and "English": Quilts from the I...

Wass, Jan

-

1850-1875

Scrap Quilt Yoder, Magdalena Fi...

-

1850-1875

Scrap Foster, Matilda Ann...

-

1876-1900

Nine Patch Gingerich, Catherin...

-

1876-1900

Nine Patch Foster, Matilda Ann...

-

1901-1929

Log Cabin Mast, Elizabeth Bri...

-

1901-1929

Log Cabin Courtho... Moore, (Mary) Clara...

-

1901-1929

Crazy quilt Beachy, Lydia J. Mi...

-

1876-1900

Crazy Moore, Mary Clara R...

-

1901-1929

Rocky Road to Cal... Yoder, Magdalena Fi...

-

1930-1949

Tangled Cobwebs Garvey, Florence Ir...

-

1930-1949

Sunshine and Shad... Schrock, Amanda Mas...

-

1930-1949

Rainbow Quilt Jones, Dorothy Wrig...

-

1950-1975

Lone Star Kauffman, Sovilla S...

-

1930-1949

Star of Bethlehem... Hewett, Emily Hethe...

-

1930-1949

Framed Star Beachy, Emma D. Yod...

-

1930-1949

Star of Contstant... Stenge, Bertha

Load More