BACK TO ESSAYS

Men and Quilts in the USA

To make a quilt is to engage in a tradition deeply entwined with the American cultural identity. Everyone knows what a quilt is, and most people have someone in their lives who makes quilts. These quiltmakers, it hardly needs mentioning, are women. To say the word “quilter” is to suggest womanhood in the same way as saying the word “cowboy” suggests manhood.

That is why people are always surprised to learn that I am a quiltmaker, surprised and a little shocked. It is slightly shocking, because I am a man who has chosen to go into a woman’s world, and not even a woman’s professional world such as nursing, but a world conceived, developed and maintained by women for the purpose of making things to give away--in other words, a world where no normal man would choose to go.

It is not just the needlework that wards off men from the quilt world, it is also the idea that quilts constitute an entire gift economy, where women buy fabric and supplies so they can make quilts as gifts for everyone around them. This idea, that a quilt is a gift, arose in the early 1800’s in the U.S.A., becoming one of the chief features of the American quilt. In Europe, the quilt was a fancy bedcovering in formal bedrooms of the well-to-do. Re-imagining quilts transformed the market from decorative items for the wealthy few to gifts for all. This conception continues today; nearly all quilts are made for someone the quilter knows and loves. Once the gift idea was encoded in the DNA of the American quilt, as it were, it became virtually certain that no man would be interested in quilts. It was an activity in which there were no economic incentives, no competitive incentives and no male company.

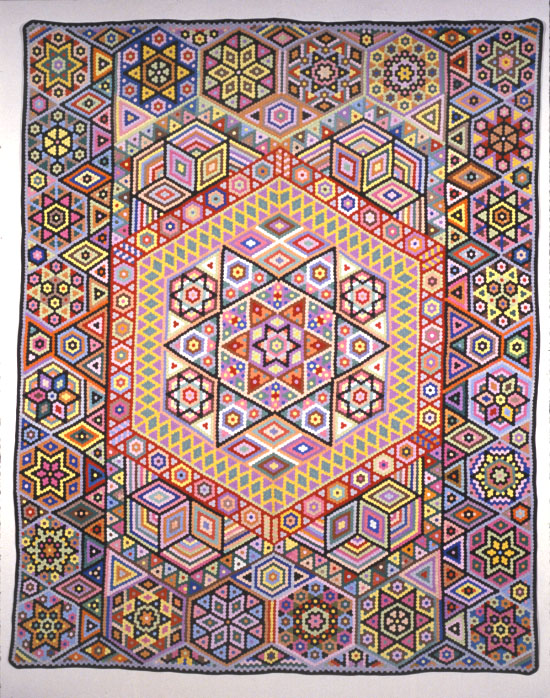

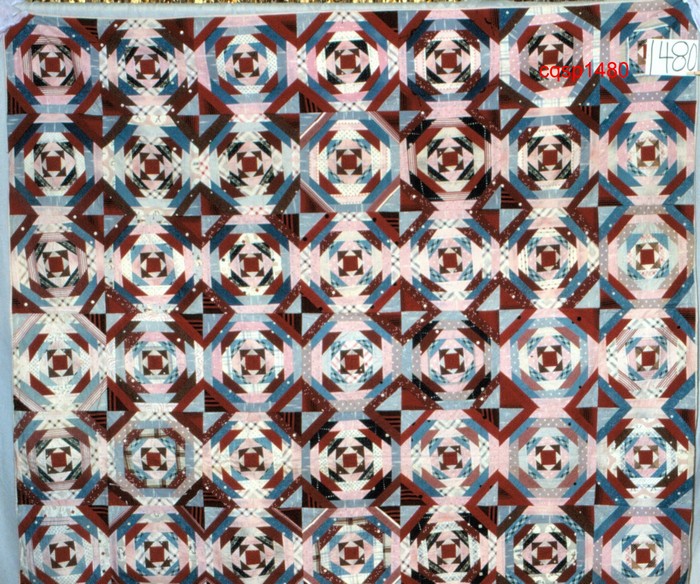

Mosaic 1

Albert Small

Ottawa, Illinois

1934

Collection of the Illinois State Museum acc.#1992.51.1

Consequently, when the few men have gone into that realm, they have often invented ways to make it a competition, so as to have a proper psychological justification for their peculiar interest. Here you can think of Albert Small, the dynamite handler from England who settled in Illinois. The Illinois Museum web site has this telling paragraph:

“In 1951, one of the headlines on a "Ripley's Believe It or Not!" newspaper column read: ‘Albert Small makes a MOSAIC quilt with the largest number of pieces ever sewed!’ Mr. Small probably enjoyed reading that headline, since he was determined that his quilts were not to be outdone.”

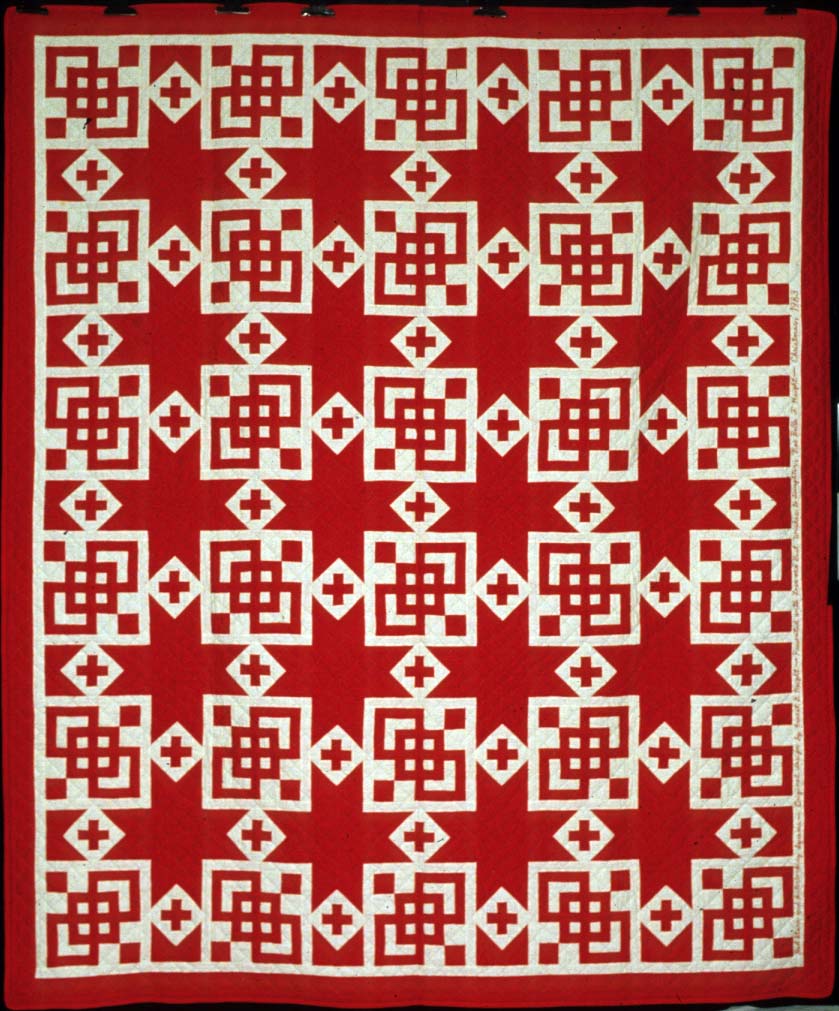

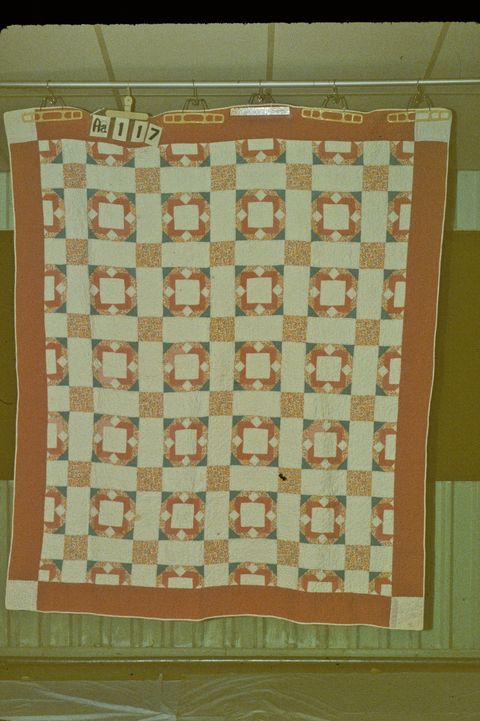

Red Stars and Interlocking Squares

Ernest Byron Haight

Butler County, Nebraska

1973

Private Collection

Or Ernest Byron Haight of David City, Nebraska, who was determined to develop new ways of piecing, quilting and designing quilts, and ended up writing the first handbook for machine quilting, Practical Machine Quilting for the Homemaker, 1974.

In my case, I did what men have done for centuries: I made a profession out of it, writing articles and books, lecturing and teaching, selling quilts. I thought it was a dashingly original and unusual way to go, until I realized I had simply followed the pattern. That is, when men go into a realm that is traditionally associated with women’s work, they tend to professionalize it. If women do all the cooking at home, men who want to cook become chefs. If women do all the decoration at home, men who want to decorate become interior designers. Women do the gardening? Men become landscape architects.

When I say I make quilts professionally, the first question women have for me is, “How did you get started doing that?” I believe the underlying thought is that if ONE man can be turned into a quilter, then maybe a bunch of them can. But the first question men have for me is, “Can you make a living doing that?” Men need to explain to themselves how another man could be involved in something so alien. If I am making money from it the issue becomes much simpler: “Oh, he does it for the money.”

While that is not exactly true, the fact remains that through a combination of hubris and naivete I did decide to become a professional quiltmaker just a few months after I had started making quilts. Not all men who take up quilts choose to go pro, of course. There is an increasing number of men who are happy to be quilt guild members, simply participating in the standard guild activities and making quilts to give away to friends and relatives.

There is, then, a wide spectrum of motivations and impulses behind men taking up the quilt. But there are a couple of elements they have in common.

First, they are members of a tiny population. There are millions of women who make quilts, and maybe a few thousand men, perhaps even fewer. In my experience, about one out of every hundred quilters is male.

Second, the burden of the tradition rests differently on men. Since quilts were developed by women in this country in a particular way, and since making quilts has remained so closely identified with women, a woman making a quilt joins a long tradition of women who did the same. She may either accept the tradition or reject it so as to free herself from its perceived restraints. Either way, the tradition is hers; it is the background against which she works. For a man to join women in quiltmaking he has to psychologically get up from the room where all the men are watching sports and go settle in across the hall where the women are sewing and talking. For some men this trip is more significant than for others, but in any case men enter the room as guests, not as members of the group that set it up and furnished it.

Another way of looking at this would be to consider that American women have made and distributed quilts for generations, an enormous legacy spontaneously carried on by wave after wave of women. If men look at the tradition at all, they find the quilt men who broke records, won contests, created new techniques. The tradition a man joins is one of exceptionalism. Like the other men who have made quilts, he can simply make up his own way of going about it.

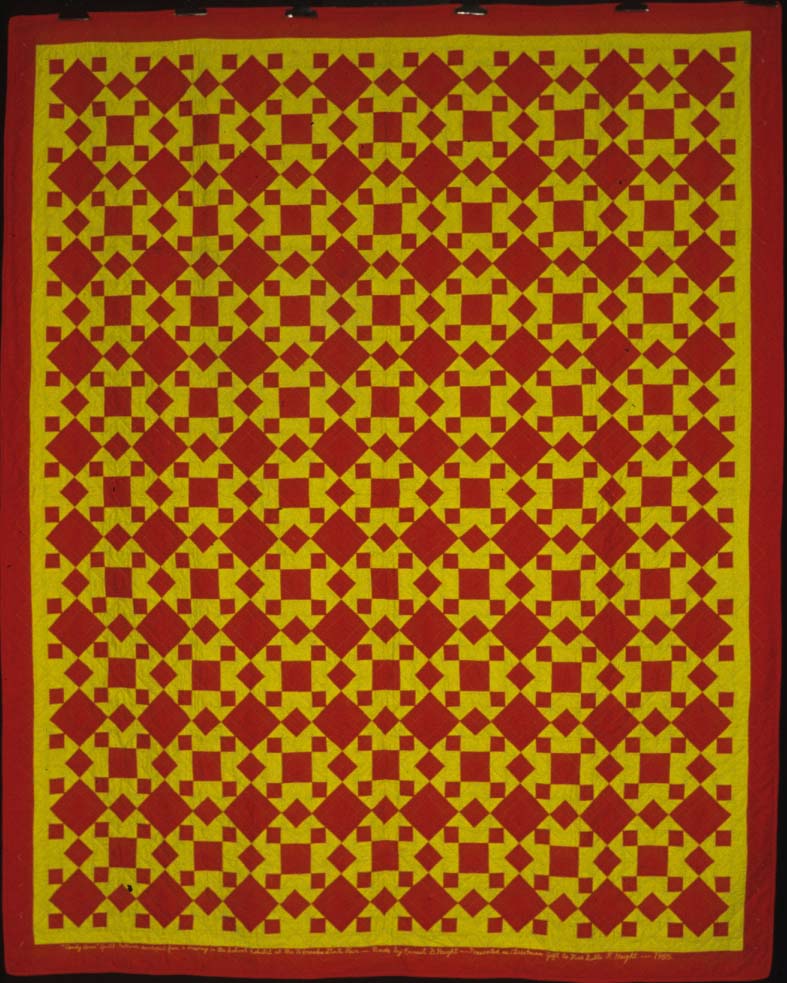

Candy Corn

Ernest Byron Haight

Antelope County, Nebraska

1968

Private Collection

Before I discovered quilts, I played guitar for a living, so I was already accustomed to the life of an artist. In 1979 I started my quilting career under the guidance of Mary Schafer, an all-around quilt scholar, historian, quiltmaker and collector. Mary often said that her goal in life was “To raise the level of quilts in the popular esteem.” (A phrase she picked up in an old quilt book.) There was a lot to learn, and I decided I would dedicate myself to the job. I tried to live up to her standards by learning how to make quilts, by studying quilt history and by promoting the story of quilts through all my writing and lectures. Still, from the start I saw myself as separate from other quilters, free from traditional constraints. Her models were the great historians and quilters of the previous 150 years. Mine were Ernest B Haight, Albert Small, Michael James and Jeff Gutcheon.

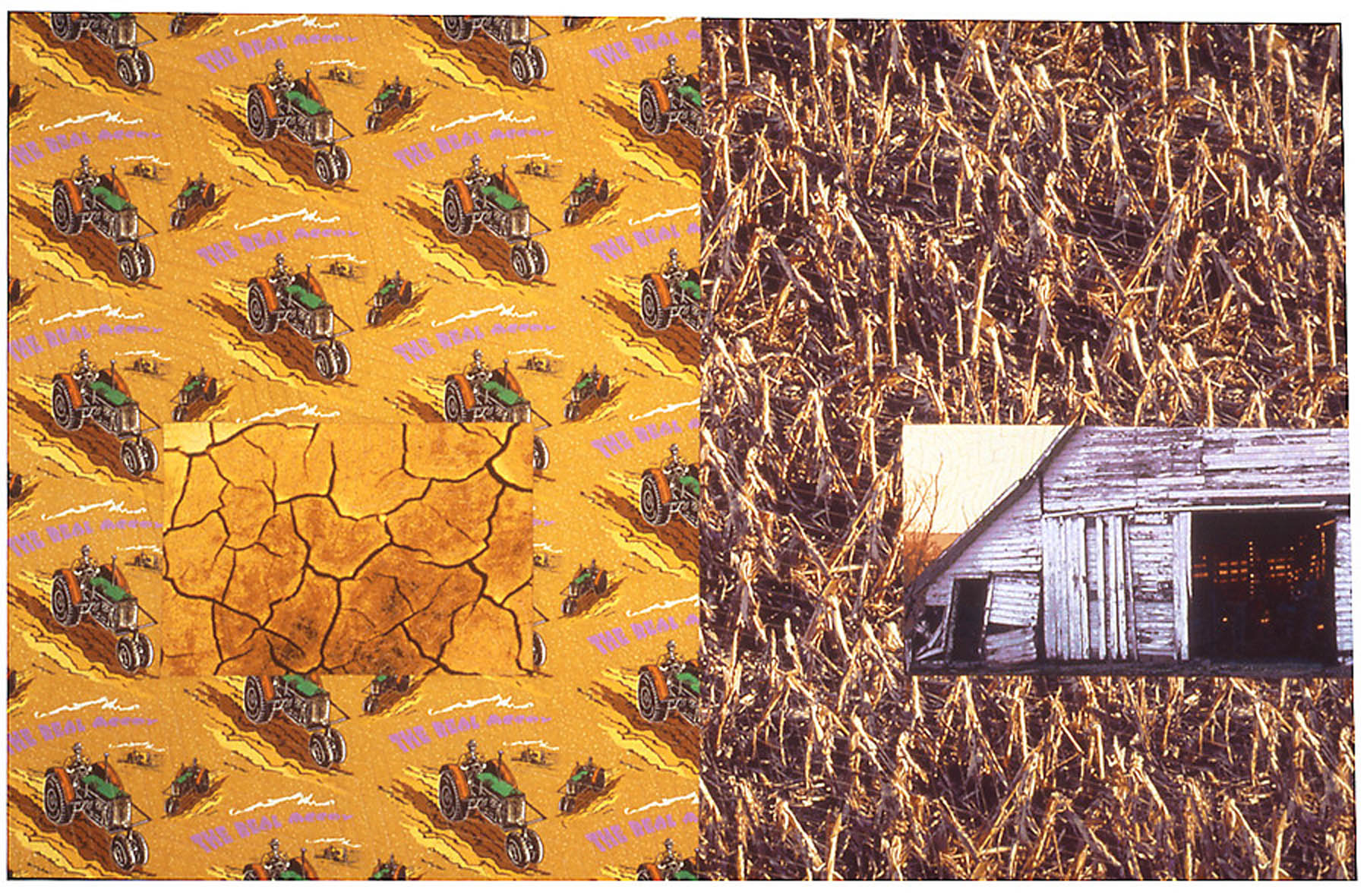

American Dream

Michael James

Colorado

2003

Collection of the Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum acc.#PQ.2005.011.001

Also, quiltmaking was something my female relatives had always done, so it was part of my own world. If they could make quilts, then surely I could. The quilt world was not intimidating like the distant art world, where talented, brilliant, fortunate people made beautiful objects for museums. And it was not the guitar world, where I was always concerned with the judgment of my peers. In quilts, my male peers were few and far apart. I was surrounded by quilters who already thought I was extraordinary just for making quilts. I always had the feeling that quilters were thrilled to have me join them, and that they were eager to hear what I had to say. Men have occasionally told me they were shut out by women at a quilt shop, or in a guild, but that has never happened to me. I have always felt welcomed and appreciated. This is an almost comic reversal of the world of hazing, ultra-competition and even ridicule women have often endured when entering a realm traditionally associated with men, such as construction, law enforcement or mechanical engineering.

The tradition, then, is there for a man to choose to join if he wishes. Conversely, he can just ignore it and do his own thing. Indeed, many of the 30 men I interviewed for my book “Men and the Art of Quiltmaking,” (AQS, 2010) told me they simply made up their own ways of working in quilts, freely creating either original techniques or original designs. I think this was only possible in our modern quilt era, when the notion of quilts as art has grown. In the past this was not an option, so men’s quilts looked pretty much like women’s quilts. Here are a few examples of very nice quilts that, to me, show no particular evidence of having been made by men:

Log Cabin, Pineapple Scrap

Charles H. Riley

Southbury, Connecticut

1930-1940

Private Collection

Sage Bud

Carl Axelson

Marquette, Kansas

1928

Private Collection

Dahlia

Stephen Kusmik

Manchester, Connecticut

1930-1945

Private Collection

In 1979, the year I was introduced to quilts, there already existed a tradition of quilts as art. Starting with Jean Ray Laury’s quilts and quilt shows from the 1950’s through the 1970’s and beyond, it was already common for quilts to be hung on walls like art. So I had no trouble perceiving them as such and choosing to follow my own path. I doubt if it would have occurred to me to go outside the tradition if I would not have seen the work of Nancy Halpern, Michael James, Nancy Crow and the rest. Once I saw the possibilities, however, I knew exactly what I wanted to do. "If these other people can make quilts any way they want," I thought, "Then I can too!"

In the end, then, it is both easier and harder for men to make quilts. It is easier because men do not have to contend with the tradition in the same way as women. It is harder to get started, in that men have to jump over the gender hurdle to get to the realm of quilts in the first place. I believe this is true at this particular moment, in mid-2011. But I also see that in America gender roles are changing rapidly and I imagine that in a few years the edges between them will become ever more blurry. You can see this happening in the blossoming world of machine quilting.

One of the biggest factors in the recent segment of quilt history has been the rise of the long arm machine. Since 1990 or so the idea of machine quilting has gone from little-known and little practiced, to ubiquitous. From a man's point of view, this introduces into quilts a large, complex piece of machinery that can be mastered, that needs maintenance, and that fairly begs for someone with an oil can and a few shop towels. Already I can see that the long arm has brought more men into quilts than any PR campaign ever could. And once they start working on the machine men seem mostly to join the quilt world in doing what women do in it. Men and women alike have innovators and pattern-followers in the long arm world.

With all this in mind, I would say that every year more men take up quilt making. But given the vast differential between the number of female quilters and the number of male quilters, I think it will be a long time before quilt guilds have equal numbers of each.

Joe Cunningham

San Francisco, 2011

All rights reserved

-

Museum

Illinois State Museum Illinois State Museum

-

Documentation Project

Nebraska Quilt Project University of Nebraska-Lincoln

-

Museum

Rocky Mountain Quilt Museum -

Documentation Project

Connecticut Quilt Search -

Documentation Project

Kansas Quilt Project Kansas State Historical Society

-

1934

Mosaic 1 Small, Albert

-

1973

Red Stars and Int... Haight, Ernest Byro...

-

1968

Original Design -... Haight, Ernest Byro...

-

2003

American Dream James, Michael

-

1930-1949

Log Cabin Riley, Charles H

-

Sage Bud Axelson, Carl

-

1930-1949

Dahlia Kusmik, Stephen

Load More