BACK TO ESSAYS

Feminism and Nationalism in the Construction of a Quilt Heritage in the United States in the 20th Century

The making of patchwork quilts is one of the most picturesque of all the folk-arts. It is the only one of the home-craft arts that has withstood the machine age. The beauty which has its expression in the work of our architects, artists, and poets of today oftentimes had its first fling in these humble creations in the hands of our pioneer mothers. Needlework was the one art which women could claim as their own.

Carrie Hall, The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt, 1935[i]

In the past 200 years, two eras have been pivotal to the formation of a narrative about American quilts: the ‘Colonial Revival’ that began in the late 19th century and extended into the 1930s, and the 1970s, a time of unusual receptiveness in the art world to non-canonical works of art, and, even more importantly, the decade of the full flowering of the so-called ‘Second Wave’ of feminism. The mythmaking and valorization of women’s work in both of these eras have bequeathed a legacy in which myth and wishful thinking compete with critically-focused historical analysis in the minds of the American public about quilts and their histories. In this essay, I explore the social history of these two eras, and the place of quilts within that history, so that we can better understand the multi-layered history that wraps around quilts.[ii]

The 1970s: the Art World, Feminism, and the Bicentennial

To understand the history and the historiography of quilts, an understanding of the events of the 1970s is crucial, and will be addressed first. In that decade, several diverse events and trends of importance to quilt history occurred, each a stone thrown in a pond, with far reaching ripples.

First, the biggest stone, with the greatest ripple effect: in 1971, Jonathan Holstein and Gail van der Hoof mounted the revelatory exhibit “Abstract Design in American Quilts”, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. This ground-breaking presentation offered quilts, heretofore seen by most as humble domestic icons, as the logical and bold precursors to the modernist visual statements of abstract painters such as Barnett Newman, Piet Mondrian, and Josef Albers. Setting attendance records at the Whitney, engendering widespread media attention, and touring North America and Europe for many years, this exhibit, its small catalogue of the same name, and the subsequent book The Pieced Quilt: An American Design Tradition (1973) were pivotal in opening the art world’s eyes—and those of the general public --to the inherent worth of quilts as art objects of considerable visual eloquence.

Arguing that “an important body of American design had been largely overlooked,” Holstein articulated the ways in which quilts participated in an American visual tradition that previously had been seen as the singular contribution of modern abstract painters. Discussing quiltmakers’ creative manipulation of geometric pattern, and the optical effects they created involving both color and form in a large-scale painterly format, Holstein deduced that “quiltmakers arrived at many visual results similar to those obtained by artists painting as much as a century later.”[iii]

In 1973 a young art historian, Patricia Mainardi, published her polemical article, “Quilts: the Great American Art,” in The Feminist Art Journal. Much reprinted, this article positioned quilts as the legitimate feminist ancestry that those interested in women’s arts in the 1970s were so avidly seeking:

Needlework is the one art in which women controlled the education of their daughters, the production of the art, and were also the audience and critics, and it is so important to women’s culture that a study of the various textile and needlework arts should occupy the same position in Women’s Studies that African art occupies in Black Studies—it is our cultural heritage. Because quilt making is so indisputably women’s art, many of the issues women artists are attempting to clarify now—questions of feminine sensibility, of originality and tradition, of individuality vs. collectivity, of content and values in art—can be illuminated by a study of this art form, its relation to the lives of the artists, and how it has been dealt with in art history.[iv]

Elsewhere in this article, Mainardi made some of the same points about quilts as Holstein, surely drawing from his research in doing so; yet she was scornful of the appropriation of quilts by male scholars and curators who wanted to bring them into the modernist conversation about art. As befitted the separatist notions of feminism common in the 1970s, Mainardi sought to position quilts solely within a female discourse (both historically and in her contemporary use of them), and to reclaim them as a cornerstone of a feminist art history:

Quilts have been underrated precisely for the same reasons that jazz, the great American music, was also for so long underrated—because the ‘wrong’ people were making it, and because these people, for sexist and racist reasons, have not been allowed to represent or define American culture.

In music it became an open scandal that while black jazz and blues musicians were ignored, their second-rate white imitators became famous and rich. Feminists must force a similar consciousness in art, for one of the revolutionary aims of the women’s cultural movement is to rewrite art history in order to acknowledge the fact that art has been made by all races and classes of women, and that art in fact is a human impulse, and not the attribute of a particular sex, race, or class.[v]

With the hindsight of three decades, it is easier to see that Holstein and Mainardi were, in at least some respects, making similar claims for the legitimacy of quilts as a great American art form, and of their makers as unchampioned artists. These two authors spoke to different (though overlapping) audiences, using different vocabularies. The subsequent interest in quilts on the part of women’s studies scholars rests in part on Mainardi’s contribution, which placed women’s handiwork within a feminist discourse.[vi] The explosion of quilt exhibits and the rise of an interest in collecting quilts derives substantially from Holstein’s considerable public achievements.[vii] The efforts of many scholars, artists, curators, and critics in the 1970s—Holstein and Mainardi among them—opened the art world to the diverse multicultural expressions we have seen there for the last thirty-five years—including quilts and other textile arts, folk and outsider arts, and numerous ethnic traditions.

The counterculture and “back to the land” movements of the 1960s and 70s led many young women to seek out handmade, rural, and folk traditions, and to emulate historical quilts by making new ones with their own hands. Mainstream women focused on America’s bicentennial celebrations of 1976 to honor the tradition of quilt-making which they saw as distinctively American, just as women had done during the Centennial of 1876.[viii]

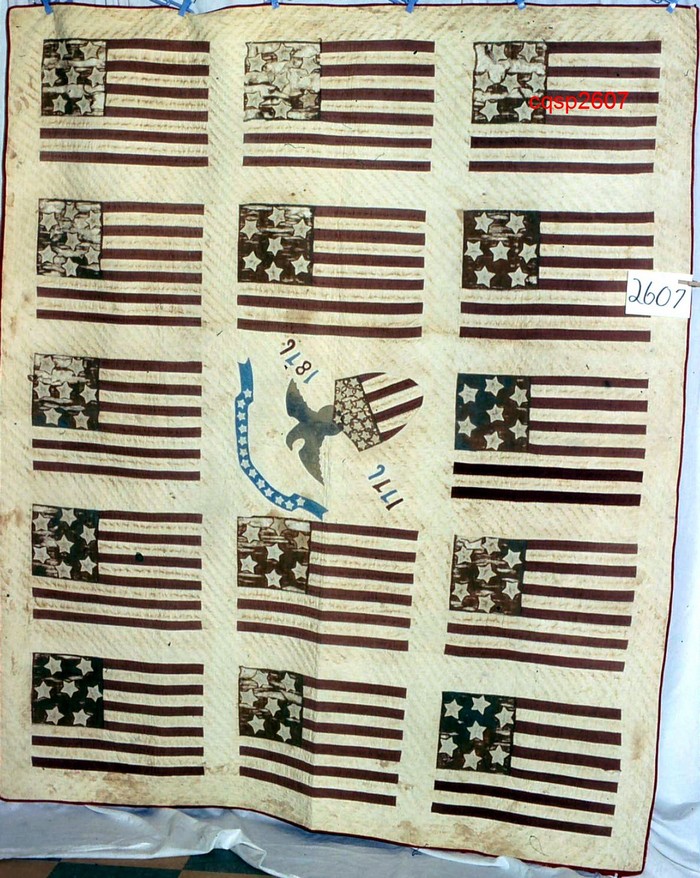

Eagle and Flags Medallion

Maker unknown

Collection of the Scott Fanton Museum acc.#76.70

Many states held exhibits emphasizing the quilt heritage of their regions. Urban quilt guilds made collective quilts, and national quilt contests flourished. There were, for example, an astonishing 10,000 entries in the Museum of American Folk Arts/ Good Housekeeping Magazine bicentennial quilt contest; members of historical societies and numerous local quilt guilds made heritage quilts, often memorializing local landmarks or historical events.[ix]

Each of these events claimed quilts as part of distinct patrimonies: Holstein and van der Hoof’s exhibits claimed them as part of the landscape of American fine arts; Mainardi claimed quilts as part of a feminist artistic legacy. And in the bicentennial year, women all across America, even those who might not embrace the language of feminism, identified themselves as sisters or granddaughters in this capacious matriliny of quilters who had long constructed an American artistic heritage with cloth. Mary Vida Schafer (1910-2006) was one such woman [See Mary Schafer essay], though she was noteworthy also as one of the many women who kept quilting alive in the mid-Twentieth century.[x] Between 1952 and 2000 she made scores of quilts, using “modern” published patterns of the mid-20th century as well as older traditional designs that she drafted herself. During the American bicentennial she made six large quilts in honor of early American women[xi] .

At this same historical moment, in different parts of the country, university-trained artists turned to pieced fabric as they looked for a road out of the impasse of modern abstract painting. California artist Jean Ray Laury, who had been making quilts and other textile arts since the 1950s, published Quilts and Coverlets: A Contemporary Approach in 1970. The first important book on quilt-making in a contemporary vein, it was illustrated with many of the author’s and other quilt artists’ designs.[xii] In 1973, Michael James earned an MFA in painting from the Rochester Institute of Technology and shortly thereafter turned to quilt-making as his artistic medium of choice. Exposed to Amish quilts through a public lecture by Holstein, James began to experiment with an Amish color palette. His 1975 work “Bedloe’s Island Pavement” married the aesthetics of Mondrian and the Amish quilter.[xiii] His work also served as a reminder that the language of quilts was not, in fact, simply a female idiom).[xiv]

All these currents swirled simultaneously, making waves in the world of art collectors, in the world of studio artists, and in the world of art historians and scholars of women’s studies. Most importantly, these waves eddied and crashed in the world of ordinary American women who chose this moment to celebrate their female artistic heritage by turning their creative energies to the making of quilts. They engendered an artistic and economic phenomenon of astonishing proportions that has continued unabated into the 21st century.[xv]

The Colonial Revival: Women’s Work, Vernacular Art and an American National Identity

As so often happens in the cultural arena, a movement that imagined itself as entirely original was, in fact, replaying and expanding upon similar impulses within a prior generation. Many decades before, an American interest in the “Colonial Revival” (starting around the time of the American centennial in 1876, and continuing into the 1930s) led museums, collectors, and the general public to reexamine the furniture, samplers, quilts and other folk arts that were part of the legacy of a “simpler” past. Like the Arts and Crafts movement, this was, in part, a reaction to the industrial revolution, in the wake of which many urban people felt disenfranchised from the pastoral, the handmade, the domestic, and the “authentic.”[xvi]

American women’s needlework was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in the “Exhibition of Antique Relics.” European ideas about the value of needlework came to America first through the work of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. In England, the Royal School of Art Needlework had been founded in 1872, and their work, also displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition, influenced, in part, the fad for richly embroidered embellishment on Crazy Quilts and Fan Quilts, which were also influenced by the remarkable displays at the Japanese Pavilion at the Exposition.[xvii] .

By the second half of the Colonial Revival era, in the period from 1913 to the 1930s, many artists and art collectors, tired of an emphasis on European modernism, turned to quilts and other folk arts as exemplars of all that was best about America and the vitality of her artistic traditions. In Ogunquit, Maine, in 1913, a group of artists established the Ogunquit School of Painting and Sculpture. They became well-known for their curious practice of decorating their little fishing-shack painting studios along Perkins Cove with weathervanes, quilts, and other inexpensive vernacular objects, finding in these simple and expressive works models for their own modernist explorations.[xviii] One factor in the interest in folk arts in the 1920s and 30s was a belief in the essential ‘Americanness’ of these objects. Europe, weakened after the devastation of World War I, seemed to Americans to be in cultural decline. American artists and intellectuals, in particular, were in search of a home-grown idiom.

John Cotton Dana of the Newark Museum had set the stage for a new way of looking at the American past in his 1914 book, American Art , by suggesting that a panoply of expressive forms could be called ‘American art.’ An abbreviated version of his list includes “…cutlery, table linen,… houses, churches, banks,…signs and posters; lamp posts and fountains; jewelry; silverware; embroidery and ribbons.”[xix] In the 1920s, Electra Havemeyer Webb was collecting the quilts and other folk arts that would, in 1947, become the Shelburne Museum in Vermont. By 1929, Henry Ford’s museum complex in Dearborn, Michigan, opened. Devoted to the history of American culture, art and industry, it, too, came to house a significant collection of quilts. That same year, Edith Halpert opened the American Folk Art Gallery in New York City, which she described as “carrying works chosen because of their definite relationship to vital elements in contemporary American art.” Just how vital that relationship was is evident in a glance at the efforts of sculptor Elie Nadelman, a Polish emigré, who, with his wealthy American wife, accumulated over 15,000 pieces of folk art by the 1930s, a collection later dispersed to many museums.[xx]

Within this circle of artists and wealthy collectors, quilts and other folk arts were seen as an art form essentially of the past, but one well worth collecting. The rhetoric of nostalgia for simpler times, when American women made quilts, may have been part of the mythos of quilts for sophisticated artists and collectors, yet in their 1935 book, The Romance of the Patchwork Quilt, Carrie Hall and Rose Kretsinger stress that quilt-making “is occupying the attention of womankind everywhere,” and that “the whole country is quilt conscious.” Dating the quilt revival to 1915, they say, “more quilts are being pieced today in the cities and on the farms than at any previous time in the history of America.”[xxi]

In a situation prefiguring the New York art world’s love affair with quilts and folk art in the 1970s, Metropolitan New York audiences were also inundated by folk art shows in the early 1930s. Most influential was “American Folk Art: the Art of the Common Man in America, 1750-1900,” held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, about which a reviewer wrote:

These extraordinary objects…are all alike in springing, untaught and carefree, from a culture that was in the making….It is impossible to regard them…without a nostalgic yearning for the beautiful simple life that is no more. Artists who find themselves growing mannered or stale will always be able to renew their appetite for expression by returning to the example of these early pioneers, and for that reason it becomes necessary for our museums to take our own primitives as seriously as they already take those of Europe.[xxii]

Much of the early rhetoric about folk art glorified ordinary working people and the fruits of their hands. Just as the larger discourse on folk traditions was full of language exalting the “naive” the “primitive” and the “untutored,” so too were early 20th century texts about quilts full of celebration for the supposedly untutored needlewomen whose work had not been fully appreciated ( a topic addressed in the next section.)

At the same time, however, quilting became a business. Many women bought professional patterns and kits, entered shows to compete for cash prizes, and decorated their colonial revival homes with quilts they made themselves. Both in the early 20th century and in the 1970s, needlework and quilt-making had a great surge in popularity as women looked to artistic genres of the past to make a statement about the present.[xxiii] A couple of the women writing influential works on quilts in the early 20th century were ardent feminists who believed that the study of women’s folk art would illuminate women’s history.[xxiv] As outlined above, another generation replayed this in the 1970s, when art world sophisticates, feminists, and ordinary women alike returned to a celebration of quilts as an important American art form. Both of these eras were fundamental in constructing an American quilt narrative that was equal parts mythology and history, fueled by nationalist ideologies and feminist pride.

Myth-making and Quilt-making: Piecing a History from Scraps

“Did you ever think, child,… how much piecin’ a quilt’s like livin’ a life? And as for sermons, why, they ain’t no better sermon to me than a patchwork quilt, and the doctrines is right there a heap plainr’n they are in the catechism.

--Aunt Jane of Kentucky, 1907[xxv]

Quilts are iconic in our American heritage precisely because they represent so many things to so many people. As symbolic objects, quilts form the backbone of an idealized story about American ingenuity and self-sufficiency in general, and female frugality, originality, and artistry in particular. Historian David Lowenthal has observed that “the pasts we alter or invent are as consequential as those we try to preserve.”[xxvi] In this section, I examine some of the often-told tales about quilts and their makers, in order to unpack the mythic history of quilts.

The legacy of the Colonial Revival in America was an idealized, simplistic quilt history in which the central figure was an illustrious craftswoman ‘making do’ with scraps. In the early 20th century, little was known about the actual history of quilts. The earliest authors of book-length quilt histories, Marie Webster (1915), Ruth Finley (1929), and Carrie Hall and Rose Kretzinger (1935) had little to rely on in terms of accurate documentation.[xxvii] They conducted their own original research, made their own collections, and relied upon the popular folklore of the day about quilts.

One of the sources upon which these authors relied was Aunt Jane of Kentucky..[xxviii] Far too often in quilt literature, “Aunt Jane” has been quoted as if she were an ethnographic informant rather than a fictional character devised by Eliza Calvert Hall (1856-1935), an activist for women’s rights and a creative writer who lived most of her life in Bowling Green, Kentucky, as the wife of a college professor. Though she published suffragist essays, she is remembered today solely for her best-selling book Aunt Jane of Kentucky (1907), an anthology of short stories which had previously appeared in national magazines.[xxix]

The eponymous heroine of the book is an unmarried 80 year old rural elder whose homespun feminism encompasses Protestant theology, the inequality of gender relations, the problems of patriarchal inheritance laws, and the ennobled domestic sphere of women’s gardens and needlework. In the most often quoted passage, Aunt Jane rhetorically asks the young female narrator who sits at her feet to learn her elder’s wisdom:

“Did you ever think, child,… how much piecin’ a quilt’s like livin’ a life? And as for sermons, why, they ain’t no better sermon to me than a patchwork quilt, and the doctrines is right there a heap plainr’n they are in the catechism. Many a time I’ve set and listened to Parson Page preachin’ about predestination and free-will, and I’ve said to myself, ‘Well, I ain’t never been through Centre College up at Danville, but if I could jest git up in the pulpit with one of my quilts, I could make it a heap plainer to folks than parson’s makin’ it with all his big words’ You see, you start out with jest so much caliker [i.e., calico]; you don’t go to the store and pick it out and buy it, but the neighbors will give you a piece here and a piece there, and you’ll have a piece left every time you cut out a dress, and you take jest what happens to come. And that’s like predestination. But when it comes to the cuttin’ out, why, you’re free to choose your own pattern. You can give the same kind o’ pieces to two persons, and one’ll make a ‘nine-patch’ and one’ll make a ‘wild goose chase,’ and there’ll be two quilts made out o’ the same kind o’ pieces, and jest as different as they can be. And that is jest the way with livin’. The Lord sends us the pieces, but we can cut ‘em and put ‘em together pretty much to suit ourselves, and there’s a heap more in the cuttin’ out and the sewin’ than there is in the caliker.”[xxx]

Aunt Jane characterizes her quilts as her diaries (a trope dear to feminist writers at the end of the 20th century, too):

You see, some folks has albums to put folks’ pictures in to remember ‘em by, and some folks has a book and writes down the things that happen every day so they won’t forgit ‘em; but, honey, these quilts is my albums and my di’ries, and whenever the weather’s bad and I can’t git out to see folks, I jest spread out my quilts and look at ‘em and study over ‘em and it’s jest like goin’ back fifty or sixty years and livin’ my life over agin.[xxxi]

Occasionally the unnamed young narrator of Aunt Jane of Kentucky pauses to add her own more sophisticated reflections, in case the reader has missed Aunt Jane’s didactic points:

I looked again at the heap of quilts. An hour ago they had been patchwork, and nothing more. But now! The old woman’s words had wrought a transformation in the homely mass of calico and silk and worsted. Patchwork? Ah, no! It was memory, imagination, history, biography, joy, sorrow, philosophy, religion, romance, realism, life, love, and death; and over all, like a halo, the love of the artist for his work and the soul’s longing for earthly immortality.[xxxii]

In the early 20th century, the belief that quilts were generally composed of scraps and re-used fabrics took hold. Writing in 1915 of pre-revolutionary era quilts (a genre for which we actually have almost no evidence)[xxxiii] Marie Webster observed, “After these gay and costly fabrics had served their time as wearing apparel, they were carefully preserved and made over into useful articles for the household.”[xxxiv] Ruth Finley wrote that a quilt originated in “the grimness of economic need.”[xxxv] Hall and Kretsinger took up this theme as well: “the pieced quilt…was familiar to most households where economy was a necessity as it was created of scrap material not otherwise of use” and “in mansion house or frontier cabin, every scrap was saved for quilt-making.”[xxxvi]

The rhetoric of “economy,” and “frugality” saturates these early texts.[xxxvii] Oddly, the quilts that the authors illustrate seldom support this position. The mythic dimension of quilts held sway to such an extent that the myth tenaciously persisted, even in the face of all material evidence to the contrary. The vast number of extant 19th century quilts are clearly made of new materials, some fabrics purchased expressly for this purpose, while others were pieces of new dress-making materials.

In the letters she wrote to her family in Vermont, Ellen Spaulding Reed (a New Englander who settled in Wisconsin with her husband in the mid-19th century) repeatedly mentions this use of new fabric. For example, on Oct 21, 1855, she wrote to her mother: “I have cut and made Willard a pair of pants, and made me a dress, and I will send you a piece.”[xxxviii] This sending of pieces of new fabric to beloved female friends and relatives was common in the 19th century, and continues today. Elaine Hedges has documented the fabric that traveled in the mail between Connecticut, New York, Wisconsin and Nebraska in the 1850s, as Hannah Shaw and her daughters kept in touch by the exchange of such mementos: “I will send you some pieces of my new dresses for patchwork,” and “Hear are some peaces for Mary’s quilt.”[xxxix]

Many 19th century quilts show strong evidence of being made from new fabric probably purchased for that express purpose. It is customary to assume that this reflects the maker’s prosperity, but an occasional anecdote reveals the sacrifices a dedicated artist of lesser means made in pursuit of her art. Lucyle Jewett recalled a story about her mother, Della Smith Jewett, and the making of a quilt in the late 19th century:

It was material to be used for a new dress, and in those early days, the girls had only one new dress a year, so it was important. But Mamma wanted to use her material to join her quilt, and told Grandma Smith so. “If thee uses thy material to join thy quilt,” said Grandma, “thee’ll have to wear thy old dress again this year.” She left it to Mamma to decide, and stated the consequences. Mamma thought it over and used the material for her quilt and wore last year’s dress again that year.[xl]

A rural 20th century Texas quiltmaker of modest means related another story that sheds light on the use of new materials in quilts. Recalling an instance in her youth, in the early 20th century, when she and her mother traveled to the dry goods store to buy some fabric for her hope chest quilts, she said:

We had picked three pieces of remnant blue and was just fingerin’ some red calico. We was jest plannin’ on enough for the middle squares from that. Just then Papa come in behind us and I guess he saw us lookin’. He just walked right past us like he wasn’t with us, right up to the clerk and said, “How much cloth is on that bolt?” The clerk said, “Twenty yards.” Papa never looked around. He just said, “I’ll take it all!” He picked up that whole bolt of red calico and carried it to the wagon. Mama and me just laughed to beat the band. Twenty yards of red. Can you imagine?[xli]

In other instances, individual 19th century quilt-makers had access to a wide range of textiles due to proximity to textile industries, their positions as workers in a factory where they were able to buy seconds and sample runs, or membership in a family of textile mill owners or dry goods merchants.[xlii]

Jonathan Holstein has addressed the “Scrap Bag Myth” of American quilts, ascribing it to an ingrained American preoccupation with a pre-industrial Golden Age of self-reliant ancestors. He points out that the vast majority of 19th century quilts have backs of whole cloth, new at the time the quilts were made,…indicating that material was purchased to make the backs, which normally would not have been seen; if quilts were truly objects in whose formation thrift and utility were the primary motives, the backs would logically have been pieced from scraps left over from home clothes production; and, if the romantic histories were true, of pieces salvaged from worn-out garments. Trust me: there is hardly a quilt maker who ever pieced any part of a quilt from sections of worn-out garments. The finished textiles would not have survived enough washings to justify either the savings on textile costs or the labor involved.[xliii]

The romanticization of the patchwork quilt was part of a larger discourse about colonial household economies, focused on even earlier women’s work like spinning and weaving, that historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has called “one of the central myths of American history.” Moreover, she argues,

The mythology of household production gave something to everyone. For sentimentalists, spinning and weaving represented the centrality of home and family, for evolutionists the triumph of civilization over savagery, for craft revivalists the harmony of labor and art, for feminists women’s untapped productive power, and for antimodernists the virtues of a bygone age. Americans expressed these ideas in local and national celebrations, in family festivals, and in craft demonstrations.[xliv]

Virginia Gunn has noted that the Scrap Bag Myth became especially entrenched during the Depression: “the tales of early colonial foremothers helping to establish a foothold in a new country by recycling worn textiles into beautiful quilts sustained women making scrap quilts in hard times.”[xlv] Indeed, the 20th century reality of rural quilters and the legacy of Depression-era quilters has helped entrench the “Scrap Bag Myth.” For these women, it is no myth, of course. Nonetheless, the idea of most quilts being made from scraps and recycled materials does not accurately reflect the real circumstances of most 19th century quilts in museum and private collections. Examination of these quilts only strengthens our belief that these are deliberate artistic constructions, composed of the finest materials within the artists’ means. Some are profligate in their use of costly silks. Others clearly show that the maker was not working out of any scrap bag, but from the latest bolts available at the dry goods store. While of course scrap quilts were made, and washed, and used up, the use of scraps was neither the defining feature nor the motivating factor in this art form, especially in the 19th century.

Just as popular literature like Aunt Jane of Kentucky lodged an idea of the romance of the rural quilter in the minds of an early 20th century audience, so too, in the 1970s, another influential book, this one non-fiction, captivated modern women’s imaginations. To write The Quilters: Women and Domestic Art, an Oral History, two Texas women, Patricia Cooper and Norma Bradley Buford, set off in search of the quilt heritage of Texas and New Mexico, interviewing elderly rural woman (average age 73) about their lives as quilters. The resulting book, an engaging and eloquent collage of first-person narratives, went through multiple editions, has been used as a textbook in Women’s Studies and American Studies courses, and was transformed into a stage play that has toured the country since 1982.[xlvi]

Cooper and Buford’s book (and the play based upon it) accurately profiles the very real histories and concerns of one type of American quilter—the rural one of modest means. While not questioning its accuracy or its excellence, I’d like to point out that this book’s enthusiastic reception reflects the continuation of that very deep American hunger for narratives about the poetry of poverty, the pride in making-do, and the homespun wisdom of the uneducated. Echoes of Aunt Jane can be heard in the words of the Texas quilter who tells Cooper and Buford:

You can’t always change things. Sometimes you don’t have no control over the way things go. Hail ruins the crops or fire burns you out. And then you’re just given so much to work with in a life and you have to do the best you can with what you got. That’s what piecing is. The materials is passed on to you or is all you can afford to buy…that’s just what’s given to you. Your fate. But the way you put them together is your business. You can put them in any order you like. Piecing is orderly. First you cut the pieces, then you arrange your pieces just like you want them. I build up the blocks and then put all the blocks together and arrange them, then I strip and post to hold them together… and finally I bind them all around and you got the whole thing made up. Finished.[xlvii]

Both at the beginning of the 20th century and at the end, we find in the discourse on quilts a use of language that seeks to ennoble the women who make them. This is understandable, given how often women’s work is ignored or trivialized, both in the popular imagination and in the scholarly literature. Nonetheless, it is worthwhile to follow this central discursive thread to see how it unspools.

As mentioned previously, several early writers on quilts were feminists, who display a gendered pride in this female artistic legacy. Eliza Hall, author of Aunt Jane of Kentucky, wrote suffragist essays; Ruth Finley, author of Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them, was an investigative reporter who wrote about the tough circumstances in which working women labored.[xlviii] It is no surprise, then, that women’s artistry should be celebrated in terms of gender partisanship in occasional passages in the early quilt books. Ruth Finley talks about quilt designs as stepping “fully into the realm of plane geometry. Ninety-nine percent of all pieced quilts represent the working out of geometrical designs, often so intricate that their effective handling reflects most creditably on the supposedly non-mathematical sex.”[xlix] Carrie Hall concurs: “Who shall say that woman’s mind is inferior to man’s, when, with no knowledge of mathematics, these women worked out geometric designs so intricate, and co-relate each patch to all others in the block?”[l]

So, too, much of the language of feminist writing of the 1970s-90s sought to ennoble and reclaim the artistic work of women who, in the words of Judy Chicago, had been “written out of history.”[li] One aspect of this post-1970 feminist reclamation project was the notion that quilts represented a counter-discourse, a covert female language that said the unsayable in a form of silent public oratory. Patricia Mainardi wrote,

In designing their quilts, women not only made beautiful and functional objects, but expressed their own convictions on a wide variety of subjects in a language for the most part comprehensible only to other women. In a sense, this was a ‘secret language’ among women, for as the story goes, there was more than one man of Tory political persuasion who slept unknowingly under his wife’s Whig Rose quilt.[lii]

This brief look into two periods of American social history suggests that quilts are one of our country’s most important artifact types. As we study “the social life of things,”[liii] we can deepen our understanding of how we shape our culture though objects, and shape our understanding of objects through the various ways we interpret and value them at different points in time.

++++

Janet Catherine Berlo (Professor of Art History at the University of Rochester) is a scholar of Native American art and women’s textile arts, as well as a quilter and creative writer. In addition to many books on Native American art, she is the author of Wild By Design: Innovation and Artistry in American Quilts (with Patricia Crews, 2003), and Quilting Lessons (a memoir, 2001).

2011, All rights reserved

++++++

-

Museum

Illinois State Museum Illinois State Museum

-

Documentation Project

Michigan Quilt Project Michigan State University

-

Documentation Project

Connecticut Quilt Search -

Legacy

Gasperik Legacy Project, Mary -

Museum

Michigan State University Museum Michigan Quilt Project

-

Ephemera

Womenfolk 10. America's Quilt Revival ...

Breneman, Judy Anne

-

1876-1900

New Nine Patch an... -

1876-1900

Eagle and Flags M... -

1975

History of Iron C... -

1975

Molly Pitcher Schafer, Mary

-

1876-1900

Crazy Fans -

1933

Grandmother's Fan... Gasperik, Mary

-

1933

Floral Bouquet Gasperik, Mary

-

1935-1940

Colonial Quilting... Gasperik, Mary

Load More